All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Rare Concurrence of Apical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy and Effusive Constrictive Pericarditis

Abstract

A 78-year-old man with a history of pulmonary tuberculosis was referred for preoperative evaluation of cardiac function. Echocardiography and cardiac cine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicated apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), a thickened visceral pericardium, and a large pericardial effusion. Cardiac late gadolinium-enhanced MRI revealed pericardial inflammation or fibrosis. Apical HCM with concurrent effusive constrictive pericarditis was diagnosed. Further studies are required to elucidate the pathophysiology of this condition.

INTRODUCTION

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a genetic disorder characterized by primary myocardial hypertrophy that affects about 0.2% of the general population [1]. Apical HCM is a rare variant of HCM characterized by hypertrophy located in the left ventricular apex that occurs at a rate of about 20% in the Japanese population [2]. Effusive constrictive pericarditis is also a rare type of pericardial disease in which a large pericardial effusion constricts the heart [3, 4]. We describe a patient with rare coincident apical HCM and effusive constrictive pericarditis.

CASE REPORT

A 78-year-old man without a family history of heart disease, sudden or premature death was planned to undergo microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia, and referred for preoperative cardiac evaluation. Pulmonary tuberculosis at the age of 20 years had been cured with antibiotics. Cough and sputum were absent upon presentation. He had been treated for atrial fibrillation with rate controlled by digoxin and warfarin since the age of 50 years. He had been examined by transthoracic echocardiography to determine the cause of dyspnea upon exertion that gradually developed at the age 68 years. However, a diagnosis was not made despite a large circumferential pericardial effusion and left ventricular hypertrophy. Adding diuretics improved the dyspnea.

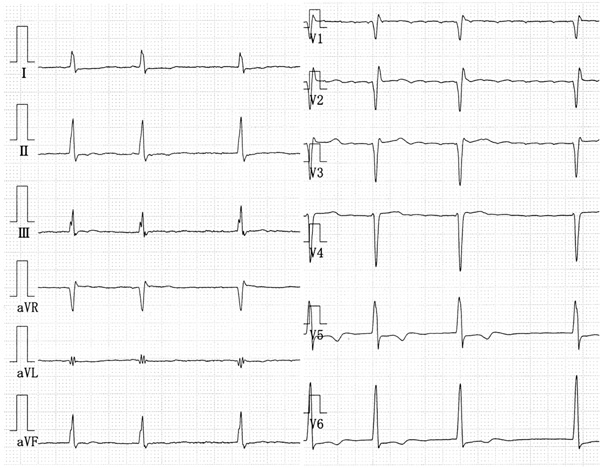

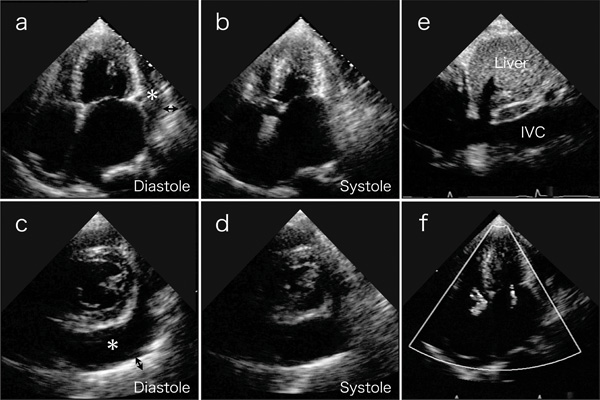

A physical examination revealed an irregular heart rate of 62 beats/min and blood pressure of 120/50 mmHg. Cardiac auscultation revealed no obvious pericardial friction sounds. Slight distension of the jugular vein, hepatomegaly and leg edema were evident. Laboratory tests revealed mild liver dysfunction and congestive heart failure (B-type natriuretic peptide value, 299 pg/ml). No serologic evidence of active tuberculosis was detected. Twelve-lead rest electrocardiography revealed atrial fibrillation, complete right bundle branch block, and slight ST depression in leads V5 and 6 (Fig. 1). Chest X-rays confirmed the absence of pericardial calcification and of findings suggesting active pulmonary tuberculosis. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a large circumferential pericardial effusion, a thickened visceral pericardium, left ventricular apical myocardial hypertrophy with normal contraction, considerable bilateral atrial dilation, and inferior vena cava dilation (Fig. 2a-e). Right atrial and ventricular collapse suggesting cardiac tamponade was not identified. Color Doppler echocardiography showed mitral and tricuspid regurgitation (Fig. 2f). These findings indicated apical HCM with a large pericardial effusion of unknown etiology.

The 12-lead rest electrocardiography shows atrial fibrillation, complete right bundle branch block, and slight ST depression in leads V5, 6.

Transthoracic echocardiography on 4-chamber views (a and b) and short axis views (c and d) reveal a large amount of circumferential pericardial effusion (asterisks), thick visceral pericardium (two-headed arrows), left ventricular apical myocardial hypertrophy with normal contraction, and bilateral severe atrial dilatation. (e) Inferior vena cava (IVC) is dilated. (f) Color-Doppler echocardiogram shows mitral and tricuspid regurgitation.

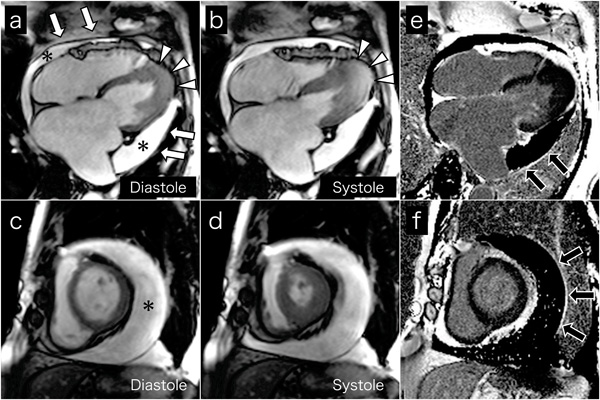

Cine MR images on 4-chamber views (a and b) and short axis views (c and d) show a large amount of circumferential pericardial effusion (asterisks), thick visceral pericardium (white arrows), left ventricular apical myocardial hypertrophy with normal contraction (arrow-heads), and bilateral severe atrial dilatation, corresponding to echocardiography. Late gadolinium-enhanced images on 4-chamber views (e) and short axis views (f) show the visceral pericardium with high signal intensity (black arrows), indicating pericardial inflammation or fibrosis.

Cardiac MRI was performed to evaluate cardiac morphology and function, and to characterize the pericardium. Cine MR images on 4-chamber (Fig. 3a and b) and short axis (Fig. 3c and d) views confirmed the echocardiography findings. High signal intensity of the visceral pericardium on late gadolinium-enhanced images indicated pericardial inflammation or fibrosis (black arrows, Fig. 3e and f). Chest and abdominal computed tomography ruled out malignant tumors. We thus concluded a diagnosis of coincident apical HCM and effusive constrictive pericarditis.

Further examinations such as Swan-Ganz catheterization, endomyocardial or pericardial biopsy and the collection of pericardial effusion were indicated to more accurately diagnose the effusive constrictive pericarditis. Pericardial fluid drainage and pericardiectomy were also indicated to improve the symptoms and hemodynamics. However, the patient and his family refused to undergo these procedures. Increased diuretics and the addition of a β-blocker improved his general condition, and an operation and postoperative course were uneventful.

DISCUSSION

We described a patient with effusive constrictive pericarditis with concurrent apical HCM, which, as far as we can ascertain, has never been reported.

Apical HCM is characterized by myocardial hypertrophy located in the left ventricular apex with decreased cavity volume and abnormal left ventricular relaxation [5]. Effusive constrictive pericarditis is characterized by cardiac constriction due to a large pericardial effusion that contributes to right ventricular failure with jugular venous distension and liver congestion [3, 4]. The coincidence of these two pathologies might additively or synergistically exacerbate biventricular diastolic dysfunction; however, the pathophysiology and patient prognosis remain unclear.

The reported etiology of effusive constrictive pericarditis is idiopathic, postsurgical, post-radiation, or associated with neoplasms or tuberculosis [6]. Our patient had been treated for pulmonary tuberculosis at the age of 20 years and although anti-tuberculosis agents could be considered as additive medical therapies, he had no clinical and laboratory data suggesting active tuberculosis at the time of referral to our hospital.

In conclusion, apical HCM and effusive constrictive pericarditis can occasionally coexist and be complicated by other issues. The pathophysiology and prognosis remain to be clarified in more patients.