RESEARCH ARTICLE

Outcomes of Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients with Previous Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Presenting with STsegment Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Pankaj Garg1, *, Hazlyna Kamaruddin1, Javaid Iqbal1, 2, Nigel Wheeldon1

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2015Volume: 9

First Page: 99

Last Page: 104

Publisher ID: TOCMJ-9-99

DOI: 10.2174/1874192401509010099

Article History:

Received Date: 22/6/2015Revision Received Date: 20/8/2015

Acceptance Date: 22/9/2015

Electronic publication date: 18/12/2015

Collection year: 2015

open-access license: This is an open access article licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/bync/ 4.0/), which permits unrestricted, non-commercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the work is properly cited.

Abstract

Background:

There are limited data on outcomes of patients with previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) presenting acutely as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI).

Objectives:

To compare outcomes in STEMI patients undergoing PPCI with or without previous CABG surgery.

Methods:

An all-comer single-centre observational registry from a cardiothoracic centre in UK. All consecutive patients presenting for PPCI between 2007 and 2012 were included. Electronic records were used to extract relevant information. Mortality data were obtained from the Office of National Statistics. Overall median follow-up period was 1.7 years (intraquartile range 0.9-2.5).

Results:

Complete data were available for 2133 (97%) patients. 47-patients had previous history of CABG. Out of these, the infarct related artery (IRA) was native vessel in 22 and graft in 25 patients. Post re-vascularization TIMI flow was inferior in CABG cohort (<TIMI 3 flow in 17% vs. 10%, p=0.012) and they were less likely to achieve acute reperfusion (TIMI 0 in 9% vs. 3%, p=0012). In-hospital-mortality was not different in both groups (2%vs.4%, p=0.23). 30-day (HR 0.54; 95%CI 0.17-1.73; P=0.301), 1-year-mortality (HR 0.77; 95%CI 0.31-1.87; P=0.56) and over a median follow-up of 1.7 years (HR 1.1; 95%CI 0.54-2.27; P=0.79) were also not different.

Conclusion:

Patients presenting with STEMI to PPCI service with history of CABG are less likely to achieve acute reperfusion and have worse angiographic outcomes. Post PPCI, the prior CABG patients do not seem to have worse shortterm and long-term prognosis.

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) leads to myocardial ischaemia, which causes significant morbidity and mortality [1, 2]. Myocardial revascularisation is the mainstay treatment of CAD for almost half a century. Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has been used in clinical practice since 1960s and is the preferred reperfusion therapy in patients with multi-vessel disease (MVD), significant left main stem disease, MVD with diabetes and patient’s with high SYNTAX scores (>22) [3-9]. Despite better use of secondary prevention measures in patients with history of CABG, the advancement of native coronary artery atherosclerosis and accelerated stenosis in saphenous vein grafts (SVG) remains an issue. Serial angiographic follow-up studies have demonstrated that approximately 10% of SVG occlude in the first year after which there is a continued deterioration, which accelerates with the grafts age [10, 11]. Deterioration in these grafts occurs at a rate of at least 2% to 5% annually [12-16]. Hence, patients with prior CABG are likely to suffer with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) because of either acute native vessel or graft occlusion.

Fibrinolytic therapy is less effective in this prior CABG population [17, 18]. In the developed world, primary percutaneous therapy (PPCI) is the preferred and most widely used intervention for patient presenting with acute STEMI. Current guidelines for patients presenting with STEMI do not explicitly describe the management of this complex group of patients, as there is limited evidence available. A sub-study of APEX-AMI (Assessment of Pexelizumab in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial showed that prior CABG patients with STEMI were less likely to undergo acute reperfusion, had worse angiographic outcome and higher 90-day mortality [19]. A sub-study of HORIZONS-AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularisation and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) also showed similar results with greater incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) and mortality at 3 years [20]. Long-term longitudinal outcomes in an unselected all-comer population have not been extensively studied. This study aimed to study the long-term outcomes of PPCI in patients with previous CABG in the real world.

METHODS

Setting. Single centre observational retrospective study from a large volume cardiothoracic centre providing PPCI service to 1.8 million population in UK.

Patients. All patients presenting for PPCI from January 2007 to June 2012 were included, with no exclusion criteria. Regional PPCI information processing database (Infoflex) for national audit of PCI was used to retrieve relevant information - patient demographics (age, sex, past medical history and risk factors for CAD) and procedural details (culprit vessel, flow after PPCI and success of procedure). The relevant medical history included the following - diabetes mellitus, smoking history, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, peripheral vascular disease, cerebro-vascular accidents, previous myocardial infarction, previous percutaneous intervention, renal disease (creatinine > 200umol/l, renal dialysis patients, functioning transplant), family history of CAD and extent of CAD. All-cause mortality till the end of study was obtained form the Office of National Statistics (ONS), UK.

Statistical analysis. Data are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables and as percentage or proportion for discrete variables. Data was summarised with descriptive statistics using Fisher Exact test for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and log-rank testing were used to compare the outcomes between CABG and non-CABG groups. Backward stepwise Cox-Regression analysis was performed to ascertain which factors influenced mortality. SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS, Inc) was used for data analysis and a two-tailed p-value of .05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Ethical Approval

This work was observational study evaluating outcomes from registry-based dataset. It was approved by the local clinical governance department as an audit project and did not require any further approval from local or national research ethics committee as per the UK guidelines.

RESULTS

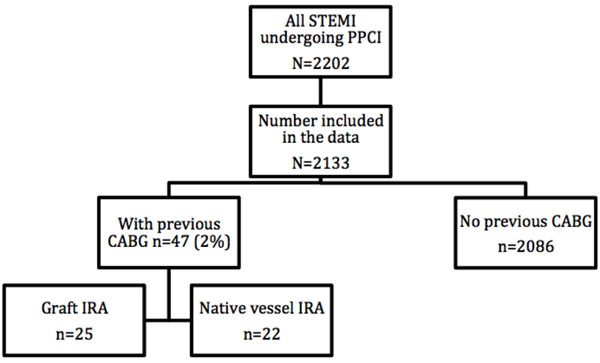

Between 2007 and 2012, a total of 2202 patients presented with STEMI to our regional PPCI centre (Fig. 1). Of these, complete data was available for 2133 (97%) patients. This group consisted of 1564 (73%) males (mean age= 61.27±12.4 years) and 569 (27%) females (mean age= 66.78±12.7 years). 47 (2%) patients had previous history of CABG. Out of these, infarct related artery (IRA) was native vessel in 22 patients and graft in the other 25 patients. Some differences were noted in baseline characteristics in the two groups - prior CABG versus no prior CABG (Table 1). Patients with no prior history of CABG were more likely to be smokers and present with single vessel disease (1VD). On the contrary, patients with prior history of CABG were more likely to have peripheral vascular disease (PVD), triple vessel disease, suffered previous MI and had previous PCI. Both group had similar representation of patients presenting with cardiogenic shock (2% versus 2%, p=1.000).

|

Fig. (1). Flow chart of number of patients recruited in each arm of the study. |

Baseline characteristics of patients presenting with STEMI to PPCI service.

| No CABG (n=2086) | Previous CABG (n=47) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1525 (73%) | 39 (83%) | 0.181 |

| Age (years) | 62.7±12.8 | 64.8±10.4 | 0.169 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 232 (11%) | 5 (11%) | 1.000 |

| Current smoker | 696 (33%) | 11 (23%) | 0.039 |

| Hypertension | 623 (30%) | 20 (43%) | 0.076 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 787 (38%) | 22 (47%) | 0.225 |

| PVD | 71 (3%) | 5 (11%) | 0.024 |

| CVA | 52 (2.5%) | 1 (2.2%) | 1.000 |

| Previous MI | 355 (17%) | 24 (51%) | <0.001 |

| Previous PCI | 136 (6%) | 11 (23%) | <0.001 |

| Renal Disease | 20 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0.375 |

| Family history of CAD | 385 (18%) | 11 (23%) | 0.446 |

| Extent of CAD | <0.001 | ||

| 1VD | 1163 (56%) | 13 (28%) | |

| 2VD | 550 (26%) | 7 (15%) | |

| 3VD | 366 (17%) | 27 (57%) | |

| Cardiogenic Shock at presentation | 44 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: PVD, peripheral vascular disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; 1VD, one vessel disease; 2VD, two-vessel disease, 3VD, triple-vessel disease; MI, myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease.

In-hospital MACCE post PPCI in both group of patients.

| Non-CABG (n=2086) |

Prior-CABG (n=47) |

P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death | 39 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 0.228 |

| MI | 4 | 0 | 1.000 |

| CVA/TIA | 2 (<0.1%) | 1 (2%) | 0.044 |

| Re-intervention | 6 (0.2%) | 0 | 1.000 |

| MACCE* | 51 (2.4%) | 3 (6.3%) | 0.11 |

* MACCE major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events defined as composite of all-cause death, myocardial infarction (MI), re-intervention and stroke.

Independent predictors of mortality.

| Variables | Hazard Ratios | Confidence Interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.06 | 95% CI 1.05-1.08 | P<0.005 |

| History of Renal disease | 2.45 | 95% CI 1.24-4.85 | P=0.01 |

| Extent of Coronary Disease | 1.23 | 95% CI 1.04-1.45 | P=0.01 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 1.59 | 95% CI 1.00-2.52 | P=0.068 |

From the 1603 patients for whom reperfusion data was available, post re-vascularization the ‘Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction’ (TIMI) flow was inferior in the prior CABG cohort (<TIMI 3 flow in 17% vs. 10%, p=0.012) and they were less likely to achieve acute reperfusion (TIMI 0 in 9% vs. 3%, p=0012).

Post PPCI, analysis of in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular and cerebral events (MACCE) showed that prior CABG patients suffered more CVA than the other group (Table 2). However, post-procedure MI, re-intervention and all-cause death did not differ significantly between the two groups.

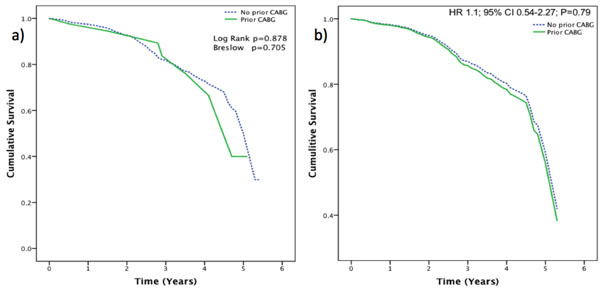

In-hospital mortality, though numerically double in CABG group, was not statistically different between the two groups (2% vs. 4%, p=0.228). Furthermore, 30-day mortality (HR 0.54; 95% CI 0.17-1.73; P=0.301) and 1-year mortality (HR 0.77; 95% CI 0.31-1.87; P=0.559) were also not different in both groups. Over the long-term follow-up (median 1.7 years), there was a trend towards higher mortality in previous CABG cohort that did not achieve statistical significance (10% vs. 17%; P=0.12). Within the prior CABG group, there was a trend towards higher mortality in the graft IRA patients versus the native IRA patients (24% vs. 9%, P=0.253).

Even after accounting for all the confounding factors using the cox-regression analysis, previous CABG history did not show any significant influence on the mortality after PPCI (HR 1.1; 95% CI 0.54-2.27; P=0.79) (Fig. 2). Independent predictors of mortality in both groups were the traditional risk factors: - older age, history of renal disease and extent of coronary artery (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This large longitudinal observational study, which collected data of patients presenting to PPCI service over a period of five and a half years, didn’t show any statistical difference in the primary outcome (death) in patients with or without previous history of CABG. As expected, patients with prior CABG were more likely to have history of previous MI, PVD, triple vessel disease and also previous coronary intervention. Interestingly, even though mortality rates in both groups didn’t achieve statistical difference, the patients with prior CABG were less likely to achieve acute reperfusion and had worse angiographic outcome as assessed by TIMI flow.

A substudy of a large trial (APEX-AMI) of PPCI in STEMI patients by Welsh et at showed increased 90-day mortality in patients with prior CABG (11.9% vs 4.9%; P<0.001) [19]. In keeping with this study we further analysed mid-term outcomes in our population and the 90-day mortality in the prior CABG patients was no worse (HR 1.06; 95% CI 0.39-2.88; P value=0.909). Hence, there is plausible difference in mortality outcomes between our study and APEX-AMI. However, similar to our study, Welsh et at showed poorer angiographic outcomes and worse TIMI flow post PPCI in CABG group. We also noted that in the substudy of APEX-AMI, PCI was performed less frequently in the CABG group (78.9% vs 93.9%).

Another large study (n=1649) performed by Bench et al in several New York hospitals showed higher in-hospital mortality in CABG group (6.5% vs 2.2%; P=0.012) and also higher rate of MACE (6.5% vs 2.7%; P=0.039) [21]. On the contrary, our study did not achieve statistical difference in both in-hospital mortality (2% vs. 4%, p=0.228) and MACE (6.3% vs 2.4%; P=0.11). This may be because our data represented smaller prior CABG group (47; 2.2%) compared to Bench et al’s study (93; 5.6%).

A substudy of HORIZONS-AMI trial also studied the long-term outcomes in both the prior CABG and the non-CABG groups presenting with STEMI to the PPCI service [20]. In this study too, no statistical difference in mortality was noted between both the groups over a follow-up period of 3 years (HR 0.37; 95% CI 0.10 - 1.34; P=0.13). This was the only other study to ours that analysed long-term outcomes in both the groups. Similar to our study, they also showed higher occurrence of CVA post PPCI in the prior CABG group (0.7% vs 2.9%; P=0.008).

For all the four studies mentioned above including ours, it is still not clear if patients with previous CABG who present to the PPCI service with STEMI have higher mortality after PCI compared to the non CABG group. Nevertheless, all studies concur that previous CABG patients are less likely to achieve acute reperfusion and have worse TIMI flow outcomes post PCI. It is also important to note that prior CABG patient’s are more likely to suffer CVA post PPCI.

The final conclusion from all the respective studies is that all patients with prior history of CABG who present with STEMI, should be offered PPCI with extra caution and informed decision about possible extra risk of stroke and poor angiographic outcome.

Study Limitations

There are several potential limitations of our study. Firstly, as this a longitudinal follow-up study, we can only comment on the median follow-up duration which was 1.7 years since we started the data collection. Secondly, as our study was a retrospective observational study, the results ought to be contemplated as hypothesis generating. Finally, even though our CABG population in the study are similar to other studies (2%), the overall number of patients in this group was small.

CONCLUSION

Patients presenting with STEMI to PPCI service with prior history of CABG are less likely to achieve acute reperfusion and have worse angiographic outcomes, particularly where infarct related artery is a graft. However, this did not result in any significant increase in the in-hospital, 30-days and 1-year mortality. Long-term follow over a median duration of 1.7 years, also did not show any significant increase in mortality in the previous CABG cohort.

ABBREVIATIONS

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.