All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Increasing Physical Activity of High Intensity to Reduce the Prevalence of Chronic Diseases and Improve Public Health

Abstract

High incidence and prevalence of chronic diseases, increasing obesity and inactivity as well as rising health expenditure represent a set of developments that cannot be considered sustainable, and will have dire long-term consequences given the increasing proportion of elderly people in our society. Based on a review of the experiences from previous large scale population-based prevention programs and the documented effects of increased physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness on chronic diseases and its risk factors, we argue that increased physical activity, especially vigorous physical activity, is a major way to reduce the prevalence of chronic diseases and improve public health. We conclude that a coordinated population-based intervention program for improved health through increased physical activity in the entire population, with a special focus on high intensity exercise, urgently needs to be implemented nationally and internationally.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic diseases are the leading causes of death and disability worldwide. Levels of physical activity are decreasing and sedentary behaviours increasing with detrimental consequences on the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes and cancer, as well as their risk factors such as hyperglycemia, hypertension and overweight [1]. According to The World Health Organisation [WHO], the prevalence of NCDs is accelerating globally, spreading across every region and pervading all socioeconomic classes [2,3]. The World Health Report from 2002 indicated that the morbidity, disability and mortality attributed to these diseases accounted for almost 60% of all deaths and 43% of the global burden of disease [2]. By 2020 their contribution is expected to rise to 73% of all deaths and 60% of the global burden of disease. Importantly, 79% of the deaths attributed to NCDs occur in the developing countries [2].

The biological risk factors for these chronic diseases are mainly caused by an unhealthy lifestyle (2). We here argue that a community-based prevention programme, with the aim to increase physical activity of high intensity, in all age groups within the population in a well-integrated manner, is a major way to control the risk factors for NCDs, and thereby improving public health and reducing health expenses.

FOUR GENERATIONS OF POPULATION-BASED PREVENTION PROGRAMMES

Carefully planned community-based prevention programmes may be an important vehicle to reduce the incidence and prevalence of chronic disease. Such population-based strategies, aimed at reducing general risk factor levels through lifestyle and environmental changes, are considered to be more cost-effective and sustainable approaches for reducing the rates of mortality and morbidity than solely relying on individual-level interventions [4]. The rationale is that a moderate lowering of risk across a large number of people will have a bigger public health impact than large risk reductions among the few at high risk. An intervention that aims to achieve community-wide health improvements should therefore aspire to moderate risk reduction across the whole population. Community based interventions have advantages over narrowly targeted strategies because most people will be exposed to their positive effect. In addition, the costs of implementation are relatively low, large-scale health systems strengthening is not needed, and those already suffering from or at high risk of NCDs will also benefit [5]. Community based interventions aim to reduce the prevalence of one or more risk factors for chronic disease, and they typically use environmental change, public education and some degree of behavioural change strategies to promote lifestyle changes [6].

The North Karelia Project in Finland [7] together with the CHAD Project [8], the Stanford Three Community Project [9] and the Franklin Community CVD Health Program [10] provided the settings for the first large-scale community intervention programs in the early 1970s. The goals of these large scale interventions were to bring about social and health-oriented behavioural changes on several levels in the community – from the individual to the institutional and organizational levels. These first generation projects inspired later programs including the Stanford Five-City Project [11], the Minnesota Heart Health Project [12], and the Pawtucket Heart Health Project [13] in the United States.

The third generation projects evolved during the 1980s and 1990s with the goal of replicating the earlier trials but using fewer resources and targeted more specifically high-risk sub-populations. Among these studies was the Finnmark Intervention Study with a specific aim of changing cardiovascular risk factors through community-based intervention in a fishing community of Båtsfjord in the Norwegian Arctic [14]. The fourth generation studies that evolved after 2000 have focused more on discrete sub-populations such as the socioeconomic deprived, rural dwellers, elderly and ethnic minorities among others [4].

OUTCOMES OF COMMUNITY-BASED PREVENTION PROGRAMMES

One of the earliest and perhaps the most cited of all programmes is the North Karelia Project which was launched in Finland in 1972 in response to the local petition to get urgent and effective help to reduce the great burden of exceptionally high coronary heart disease (CHD) mortality rates in the area. In cooperation with local and national authorities and experts, as well as with WHO, the North Karelia Project was formulated and implemented to carry out a comprehensive intervention through the community organizations and the action of the people themselves. Comprehensive activities were used, involving health and other services, schools, innovative media campaigns, local media, supermarkets, food industry, and agriculture. The population’s risk factors were greatly reduced, and consequently the age-adjusted CHD mortality rate among the 30-64 year old male population was reduced, from 1970 to 1995, by 73% in North Karelia compared to 65% in all of Finland [15]. Very favourable changes were also shown with cancer and all-cause mortality and the general health of the population. After the original project period (1972-77), the experiences have actively been used for national comprehensive action.

The favourable results from North Karelia have later been questioned because subsequent analysis showed that the decline in CHD mortality in the rest of Finland was equivalent compared to North Karelia [16]. Furthermore, North Karelia had exceptionally high coronary heart disease mortality rates prior to the intervention, which probably offered a larger potential with respect to intervention effects compared to what could be expected in other communities. Also, several of the other large-scale cardiovascular community-intervention programs including the Minnesota, Stanford, and Pawtucket projects [11-13] showed beneficial changes in cardiovascular risk factors, but they too experienced difficulties in demonstrating significant differences compared with changes in the control communities. This is probably to some extent due to crossover of information, i.e. “contamination” effects. Also, results of previous community-intervention programs are often based on subjective self-reporting. The statistical differences will be diluted due to the potential biases [e.g., social desirability] of this method. One other explanation may be that during the last decades there has been an obvious secular trend for reductions in blood pressure, cholesterol levels and prevalence of cigarette smoking, which has in turn reduced the total cardiovascular risk burden [17]. Despite this secular trend, there is evidence that community-based interventions have an additional beneficial effect on these three risk factors [7,9,18,19], although some studies did not support this (Table 1). The role of prevention programmes in initiating and accelerating the favourable events should nevertheless be recognised. The results with regard to effects on mortality rates [10,11,20], body mass index [BMI] [8,9,12,19], and physical activity [12,14,21] are less consistent (Table 1).

Studies Reporting Effect or no Significant Effect on Parameters Relevant to Public Health

| Parameter | Effect | No Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality | [82, 10, 83, 84] | [20, 11, 85] |

| Estimated CVD risk | [82, 9, 10, 86, 87, 84] | [11, 20, 13, 85] |

| Type II Diabetes | [88] | [85] |

| Blood pressure | [7-11] [83, 85, 18, 88, 14, 89, 87, 84, 19, 90] | [91, 12, 13, 86] |

| Cholesterol levels | [7 , 9, 10, 83, 18, 88, 86, 89, 87, 19, 90] | [91, 8, 12, 13, 11, 85, 14] |

| Smoking | [7, 91, 8, 9, 92, 10, 18, 88, 84, 85, 19] | [11-14, 93, 89, 94, 95-97] |

| Body mass index | [8, 13, 86, 19, 90] | [91, 9, 12, 18, 14, 88, 89, 93, 94, 85, 97] |

| Physical activity | [12, 88, 14, 97, 19] | [98, 21, 85, 86, 95, 93, 96, 94] |

WHO Recommendations on PA for Health, Adapted from WHO Report 2010 (1]

| 5-17 Years Old |

|

| 18-64 Years Old |

|

| 65 Years and Above |

|

| PA = Physical activity |

A RISING PANDEMIC OF OVERWEIGHT AND OBESITY

Overweight and obesity are emerging as a pandemic [22-24] and imposing a large economic burden on society, responsible for about 80 % of type 2 diabetes, 35% of ischemic heart disease and 55% of hypertensive disease in Europe [24]. According to WHO, the prevalence of obesity in Europe has tripled in the last two decades and the obesity trend is especially alarming in children and adolescents, as there are ten times as many obese in this age group in 2005 than in the 1970’s [24]. In line with these trends, the latest figures from the Health Survey of Nord-Trøndelag (HUNT) in Norway showed that 60% of the population now can be classified as overweight, of which a third can be classified as obese. The proportion of obese men in Norway has tripled in the last 20 years (unpublished data, www.hunt3.no) and the incidence and prevalence of type 2 diabetes has consequently increased in Norway in recent decades. In 2004, diabetes prevalence in Norway was estimated based on several population-based surveys and it was found that between 90.000 and 120.000 Norwegians suffered from type 2 diabetes. It was estimated that as many people have an undiagnosed type 2 diabetes [25]. Unpublished data from the latest HUNT survey (HUNT 3) indicated that the incidence of type 2 diabetes continues to increase, especially for men. In the long run, this will probably result in an increase in diabetes-related complications such as heart- and kidney disease. Extensive studies have demonstrated that both weight loss and physical activity can reduce the development and incidence of type 2 diabetes [26-28] and that this may be more effective than drug therapy [29].

INACTIVITY

Physical inactivity is now the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality [1]. Recent reports from England and the United States indicated that physical inactivity is the most common risk factor for chronic disease given that, when measured objectively, 95% of the adult population does not comply with their national recommendations of physical activity [30,31]. In England, the estimated costs related to physical inactivity is five times higher than the costs related to smoking [32] and in 2000, the annual direct cost of physical inactivity in the USA was estimated as $76.6 billion [33]. In view of the importance of inactivity for morbidity and mortality, it has recently been suggested that physical inactivity per se should be regarded as a disease [34]. In 2009, 83% of Norwegian 9-year-olds and 52% of 15-year-olds met the national recommendations for daily physical activity [35]. Norwegian boys in middle school and high school report 37-43 hours sedentary behavior in front of the PC or TV per week outside school hours in 2005, which represented a doubling from 1997. For girls the same age, the figure is 30 hours per week, also doubled from 1997 [36]. Generally, only about 20% of the Norwegian adult population (varies with gender and age) meets current recommendations for physical activity [35].

EFFECTS OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

Most previous community-based intervention studies have implemented multifactorial risk factor programs, including health education, to increase risk factor awareness, reduce smoking, and change dietary habits as well as screening to directly target blood pressure and cholesterol levels. Although several studies have estimated the effect of intervention on physical activity level and body weight, few of these have documented positive outcomes for these parameters (Table 1). This is probably in part due to the secular trend of a more sedentary lifestyle, but also attributable to the lack of thoroughly organized, integrated, long-term interventions to increase physical activity in the whole population. There is vast potential for reducing morbidity, premature mortality, and health care costs by increasing physical activity. Increased physical activity can actually reduce mortality similarly to smoking cessation [37]. In a recent study involving 416 175 individuals, physical activity for 15 min a day or 90 min a week provided a reduction in all-cause and all-cancer mortality and extended an individual's lifespan for an average of 3 years [38]. This minimum amount of exercise was found to be applicable to men and women of all ages, even those with cardiovascular diseases or lifestyle risks.

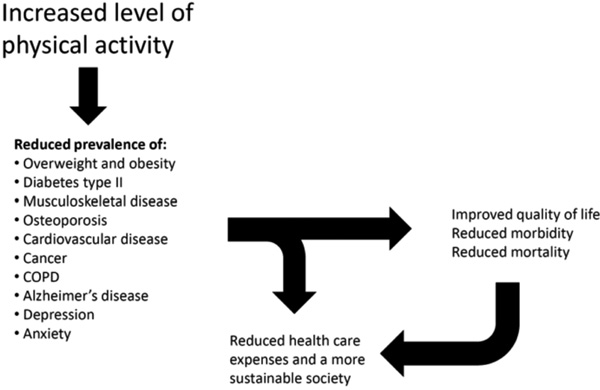

It is well documented that increased physical activity reduces blood pressure [39] and cholesterol levels [40] as well as increases insulin sensitivity, thereby reducing the risk of developing type 2 diabetes [28]. Furthermore, regular physical activity may reduce body weight or prevent weight gain and bring about beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system [40]. Studies have documented that increased aerobic capacity [cardiorespiratory fitness; CRF] and physical activity leads to decreased morbidity and mortality, both in the healthy population [41-43] and in high prevalence patient groups as represented by patients with ischemic heart disease [44] chronic heart failure [45,46] and COPD [47]. Recent studies also showed that physical activity is associated with reduced risk of developing a variety of conditions and diseases such as metabolic syndrome, breast cancer, colon cancer, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, diabetes, high blood pressure, asthma, arthritis, osteoporosis and Alzheimer's disease by as much as 40-60% [48] (Fig. 1). Individuals with at least average CRF for gender and age live longer than those with lower fitness, and even small changes in fitness can provide significantly increased life expectancy [49,50]. Interestingly, results from the HUNT survey including over 56 000 men and women showed that one vigorous workout a week was associated with a 39% reduction in mortality for men and 51% reduction in mortality for women [51].

Beneficial effects of increased physical activity in the population.

HOW TO EFFECTIVELY IMPROVE CARDIORESPIRATORY FITNESS (CRF)?

It is well documented that higher levels of physical activity and increased CRF are highly protective and are related to reduced all-cause mortality even in the face of other traditional risk factors [49,51-62]. Body mass index (BMI) can be high, but if people have at least moderate levels of CRF, the risk is lower, even compared with people with normal BMI but with lower CRF [63-65]. Interestingly, an innate low CRF is genetically accompanied by increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) [66], and CRF seems to be more important than physical activity in controlling cardiovascular disease risk factors [59,64,67,68]. A recent study [68] emphasizes the very strong association of cardiovascular risk factors with real measures of CRF and a more modest association with self-reported level of physical activity. Even though there is a dose-response relation when it comes to the effect of physical activity on CVD and its risk factors [56-58,69-71], it seems well documented that the intensity of the physical activity performed is of particular importance for its preventive effect [51,59,72,73]. As recently reviewed [74], the effects of high intensity training, such as interval training, is superior to that of training with low and moderate intensity. This indicates that an intervention on physical activity should focus on increasing CRF in the general population and include a fair proportion of physical activity with high intensity.

Interval training may be an effective way to implement high exercise intensity to increase aerobic exercise capacity and improve health. The principle of interval training is based upon high intensity exercise bouts that are alternated by periods of lower intensities that allow for recovery, making a person able to reengage in high-intensity exercise. Such “intervals,” when repeated several times, may maximize the training stimulus, as it is the accumulated time in the high intensity exercise zone that is believed to determine the outcome of the training. Informal comments from exercising subjects in our study group indicate that both healthy individuals and patients find it motivating to have a varied procedure to follow during each training session, whereas those performing moderate exercise find it “quite boring” to walk continuously during the whole exercise period. Our results show that the cardiovascular beneficial effects of aerobic exercise training are intensity dependent, with superiority of high aerobic intensity to low to moderate intensity. This is found both in patients with established heart disease such as CHD and even in heart failure [73,75]. There seems to be a true dose-response relationship regarding exercise intensity for improving exercise capacity, where high-intensity exercise training conferring about twice the benefit of moderate-intensity exercise training [74]. High-intensity exercise training may also be required for an effect to occur on left ventricular structure and function. Moreover, in patients with heart failure, a reversal of the pathological remodelling and systolic and diastolic improvements were observed only after high-intensity exercise training [73].

Winett et al. have previously demonstrated that most of the effect of aerobic training is attained when the high-intensity threshold is passed for only a few minutes [76]. This implies that the time for effective exercise can be substantially reduced. In fact, a recent study [77] evaluated the effects of one single 4- minute aerobic interval work-bout (1-AIT) carried out 3 times per week for 10 weeks. The subjects were healthy, young men, slightly overweight and the results were compared with a 4 x 4 minute training protocol (4-AIT) conducted 3 times per week in the same period. There were no differences between the 1-AIT group and the 4-AIT group with respect to effects on maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max), stroke volume, arterial blood pressure, body fat and fasting glucose levels. In addition, work from Martin Gibala’s group [78] suggests that a number of metabolic adaptations usually associated with traditional high-volume endurance training can be induced faster than previously thought with a surprisingly small volume of high intensity exercise.The available data on high intensity training and interval training so far are promising in both healthy individuals and patients, showing that even people with serious risk factors such as CHD patients, can tolerate and respond to this type of exercise training [74]. When comparing almost 200 000 training sessions involving both moderate- and high intensity training, the risk of major complications does not seem to be elevated in CHD patients performing high intensity exercise compared to moderate exercise (unpublished data). We thus believe there is sufficient empirical support to use high intensity exercise to promote health in a coordinated population-based intervention to maximize CRF. In line with this, WHO recently published a report on global recommendations on physical activity for health [1], which emphasizes that central role of high intensity exercise. As for the type of training, duration, intensity and total training load per week, we believe the guidelines presented in this report should form the basis of such a population-based intervention (Table 2).

A CALL FOR INCREASED PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

We believe overweight/obesity and physical inactivity represent a major future health challenge to the modern society, and that a large scale, community based prevention programme to increase physical activity in all age groups in a well integrated manner is required. The question today is not whether physical activity per se has the beneficial effects described above. The question is if and how a sufficient level of high intensity physical activity can be attained in all strata of the population. A coordinated population-based intervention could demonstrate positive effects of increased physical activity on public health by reducing the prevalence of NCDs, reducing medical expenses and mortality, as well as increasing work capacity in the population, which in turn would reduce socio-economic costs. This could form the basis for national and international implementation of health policies and programmatic measures to ensure sustainable development and stability.

KEY CONCEPTS OF SUCCESSFUL INTERVENTION

One of the lessons from previous large community health interventions is that when you try to do too much with too many people, the focus of the program may be lost, the dose per person is low, and the outcomes are often disappointing. When reviewing the literature in the field of population-based prevention, the general consensus is that the majority of projects have only modest impacts on the prevalence of CHD risk factors at the community level [4]. To achieve an effective intervention, one has to do the right thing, and do enough of it. This means that it is waste of resources if, for example, a correct preventive dose is used but in an intervention that has a too wide focus. Therefore, important considerations are whether interventions are doing the right things for the right people, in the right place and at the right time [4]. To achieve success, the unique contextual [social, physical, economic, political and cultural] features of the target population need to be identified instead of solely replicating previous interventions in a new setting [79]. A recent scientific statement from the American Heart Association [80] provided evidence-based recommendations on how to implement interventions to promote physical activity. This statement emphasized the importance of cognitive-behavioural strategies and the necessity of changes in health care policy in order to promote and make it feasible for the general population to follow the recommendations on physical activity. Based on research from the past decades, knowledge has been gained on how to effectively reduce the major physiological risk factors on an individual level through lifestyle modifications using exercise training. We believe that the time to introducing high-intensity exercise to the whole community has come.

A population-based intervention to increase physical activity in the population should, to the extent possible, make use of existing community structures such as schools, workplaces, sport clubs and the existing health care system, particularly the general practitioners. One should aim at increasing physical activity in all age groups by providing optimal conditions for each subpopulation. For the younger age groups this type of physical activity could for example be implemented in the school curriculum. For the middle aged and elderly training could be organized at workplaces, within sport clubs or by local authorities. In contrast to most previous large-scale population-based intervention programs, we believe that introducing a single focus, namely increased physical activity with high exercise intensity, will increase the chance of a successful intervention irrespective of whether or not the current recommendations on exercise-dose is being fulfilled. For long-term prevention, it is crucial that the intervention has an effect on the already inactive individuals, regardless of age. As early intervention has the greatest potential in a long perspective, one should focus strongly to intervene from childhood and adolescence. This will be particularly challenging and requires simple and feasible measures and activities. Various ways to implement brief periods of high-intensity physical activities throughout the day for all age groups to increase the magnitude of the exercise response should be devised. Use of the social structures described above, combined with personalized recommendations that are perceived as affordable and feasible for the individual, organizations and communities, and the society, and with opportunities for follow-up, will be important.

Evaluating the effect of the various measures, and adjust, remove or introduce measures accordingly is of utmost importance. In addition to results in the short-term that can guide the choice of measures at national level, one should also evaluate the effects over several decades, to fully assess the effect of primary prevention from young age. Thorough documentation of intervention effects, including controlling for national and international trends, necessitates a comparison with national registries on cause of death and prevalence of non-communicable diseases. Comprehensive national registries would also provide background knowledge so that intervention measures could be customized to the contextual features of the target population.

Furthermore, although having received far less attention in disease prevention, resistance training should be included in a community-based prevention programme, as it has been shown to be likely as effective as aerobic training in lowering risk for several chronic diseases [81]. In addition, resistance training is important to increase, maintain or slow the loss of muscle mass. Thus, resistance training offers an antisarcopenic effect which is of particular importance given the aging population. As an integral part of a community-based prevention programme, resistance training should be simple, brief and feasible in order to have large public health relevance.

CONCLUSION

High incidence and prevalence of chronic diseases, increasing obesity and inactivity as well as rising health expenditure plus the increasing proportion of elderly people in our society represent a set of developments that cannot be considered sustainable and will have dire long-term consequences. Physical inactivity is among the lifestyle factors most strongly associated with a low level of exercise capacity, all-cause mortality and death from cardiovascular disease. Increased physical activity, and in particular increased CRF, has a beneficial effect on all risk factors for chronic disease and premature death. A coordinated population-based intervention program for improved health and reduced health expenses through increased physical activity in the entire population urgently needs to be implemented nationally and internationally.

A special focus on high exercise intensity should be emphasized as the health benefits seem to be larger with high intensity training, specifically forms of interval training.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None declared