All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Effect of Age on Clinical Presentation and Outcome of Patients Hospitalized with Acute Coronary Syndrome: A 20-Year Registry in a Middle Eastern Country

Abstract

Introduction:

Despite the fact that the elderly constitute an increasingly important group of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), they are often excluded from clinical trials and are underrepresented in clinical registries.

Aims:

To evaluate the impact of age in patients hospitalized with ACS.

Methods:

Data collected for all patients presenting with ACS (n=16,744) who were admitted in Qatar during the period (1991-2010) and were analyzed according to age into 3 groups (≤50 years [41.4%], 51-70 years [48.7%] and >70 years [9.8%]).

Results:

Older patients were more likely to be women and have hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and renal failure, while younger patients were more likely to be smokers. Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction and heart failure were more prevalent in older patients. Older age was associated with undertreatment with evidence-based therapies and had higher mortality rate. Age was independent predictor for mortality. Over the study period, the relative reduction in mortality rates was higher in the younger compared with the older patients (61, 45.9 and 35.5%).

Conclusions:

Despite being a higher-risk group, older patients were undertreated with evidence based therapy and had worse short-term outcome. Guidelines adherence and improvement in hospital care for elderly patients with ACS may potentially reduce morbidity and mortality.

INTRODUCTION

Age is the most important determinant of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) outcomes [1]. Approximately 33% of all ACS episodes occur in patients over 75 years and they account for about 60% of the overall mortality [2]. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) reported 89.9% of the in-hospital prognostic outcome can be attributed to 8 parameters; one of which is age [3]. The burden of coronary artery disease (CAD) will increase in the next few years with an ageing population. Furthermore, cardiovascular medication side effects are more common in elderly patients due to differences in drug absorption, metabolism, distribution and excretion. Therefore, selecting treatment to avoid adverse drug interactions as well as ensuring appropriate dose adjustment in older patients is crucial [1]. Moreover, adverse events are more common in the elderly. The complication rates of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), thrombolysis, anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapies exceed that observed in younger patients [1]. Unfortunately, elderly patients, who are at a high risk of morbidity and mortality from ACS, are being treated suboptimally (treatment-risk paradox) [4,5].

In the present study we evaluate the impact of age on the clinical presentation, management and in-hospital outcomes in a large sample of patients hospitalized with ACS in a Middle-eastern country over a 20-year period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Setting

Qatar has a population of about 1.6 million (2010 census), consisting of Qatari and other Middle-Eastern Arabs (<40%) and non-Middle-Eastern individuals. The vast majority of the latter population is mainly from India, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh.

The present study was based at Hamad General Hospital, Doha, Qatar. This hospital provides inpatient and outpatient tertiary care in medicine and surgery for the residents of Qatar; nationals and expatriates where more than 95% of cardiac patients are treated in the country making it an ideal center for population-based studies. The vast majority of ACS and heart failure (HF) patients (>95%) are admitted to this hospital. In the last decade of the 20th century, cardiovascular diseases were the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the country [6].

The Cardiology and Cardiovascular Surgery Database maintained electronically at Hamad General Hospital from January 1991 to December, 2010 was used for this study. Cardiology Inpatient Data forms were completed by physicians at the time of patient discharge from the hospital according to predefined criteria. These records have been coded and registered at the cardiology department since January 1991 [7,8]. Data registered into a computer by a data entry operator were randomly checked by physicians at the cardiology department.

Patients were divided into 3 groups according to their age: ≤50, 51-70 and >70 years. Ethical clearance was obtained from the MRC Research Committee, HMC.

DEFINITIONS

Diagnosis of the different types of ACS and definitions of data variables were based on the American College of Cardiology (ACC) clinical data standards [9]. Use of adjunct therapy during hospitalization was recorded for every patient. The presence of diabetes mellitus (DM) was determined by the documentation in the patient’s previous or current medical record of a documented diagnosis of DM that had been treated with medication or insulin. The presence of dyslipidemia was determined by the demonstration of a fasting cholesterol > 5.2 mmol/L in the patient’s medical record, or any history of treatment of dyslipidemia by the patient’s physician. Chronic renal impairment was defined as creatinine >1.5 upper normal range (124 µmol/L). The presence of hypertension (HTN) was determined by any documentation in the medical record of HTN or if the patient was on treatment. Smoking history: patients were divided into current cigarette smokers, past smokers (defined as more than 6 months abstinence from smoking) and those who never smoked [7].

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data were presented in the form of frequency and percentages for categorical variables and mean ± standard deviation (SD) for interval variables. Baseline demographic characteristics, past medical history, clinical presentation, medical therapy, cardiac procedures and clinical outcomes were compared between the 3 age groups (≤50, 51-70 and >70 years). Statistical analyses were conducted using One Way ANOVA for interval variables and Pearson chi-square (χ2) tests for categorical variables. Variables influencing in-hospital mortality was assessed with multiple logistic regressions enter method. Adjusted Odds Ratios (OR), 95% CI, and p values were reported for significant predictors. All p values were 2-tailed and values <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19.0 was used for the analysis.

RESULTS

Between the years 1991 to end of 2010, 16,744 of patients were admitted with ACS. 6946 (41.5%) patients of them were aged ≤50 years, 8158 (48.7%) were between 51 and 70 years and 1640 (9.8%) patients were >70 years old.7200 (43%) patients presented with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI), 5577 (33%) patients with Non-ST elevation MI and 3967 (24%) patients with unstable angina (UA).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND BASELINE PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS (TABLE 1)

ACS Patient Characteristics and Co-morbidities According to Age

| Variables | Age≤50 Years | Age 51-70 Years | Age >70 Years | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 6946(41.5) | 8158(48.7) | 1640(9.8) | |

| Sex (female) | 410(5.9) | 1510(18.5) | 553(33.7) | 0.001 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors (%) | ||||

| • Hypertension | 1871(26.9) | 4011(49.2) | 1015(61.9) | 0.001 |

| • Diabetes mellitus | 1984(28.6) | 4095(50.2) | 882(53.8) | 0.001 |

| • Dyslipidemia | 1510(21.7) | 1726(21.2) | 320(19.5) | 0.14 |

| • Current smoker | 3104(44.7) | 2309(28.3) | 176(10.7) | 0.001 |

| • Chronic Renal impairment | 68(1) | 334(4.1) | 159(9.7) | 0.001 |

| • Family history of CAD | 222(3.2) | 154(1.9) | 21(1.3) | 0.001 |

| Prior cardiovascular disease (%) | ||||

| • Prior MI | 781(11.2) | 1579(19.4) | 429(26.2) | 0.001 |

| • Prior PCI | 800(11.5) | 859(10.5) | 82(5) | 0.001 |

| • Prior CABG> | 124(1.8) | 449(5.5) | 120(7.3) | 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.2±1.3 | 4.9±1.2 | 4.5±1.2 | 0.001 |

| Serum triglyceride (mmol/L) | 2.2±1.3 | 1.9±1.1 | 1.5±0.8 | 0.001 |

| Low density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 3.1±1.1 | 2.8±1.1 | 2.5±0.9 | 0.001 |

| High density lipoprotein (mmol/L) | 0.97±0.3 | 1.02±0.3 | 1.1±0.4 | 0.001 |

| Troponin T (ng/ml) | 40.6 | 44 | 43.6 | |

| CK-MB (u/L) | 270±795 | 204±710 | 143±675 | |

| Atypical chest pain (%) | 864(12.4) | 1010(12.4) | 163(9.9) | 0.02 |

| Ischemic chest pain (%) | 5397(77.7) | 6079(74.5) | 1042(63.5) | 0.001 |

| Palpitations (%) | 114(1.6) | 186(2.3) | 60(3.7) | 0.001 |

| Dizziness (%) | 137(2) | 189(2.3) | 33(2.0) | 0.32 |

| Shortness of breath (%) | 434(6.2) | 1286(15.8) | 467(28.5) | 0.001 |

| ST-elevation MI (%) | 3695(53.2) | 3098(38) | 407(24.8) | |

| NST- elevation MI (%) | 1872(27) | 2918(35.8) | 787(48) | |

| Unstable angina (%) | 1379(19.9) | 2142(26.3) | 446(27.2) | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass surgery; NST-elevation, non ST elevation.

In-hospital Management and Discharge Medication According to Age

| Variables Number (%) | Age ≤50 Years | Age 51-70 Years | Age > 70 Years | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st 24 h therapy | ||||

| • Aspirin | 6424(92.5) | 7365(90.3) | 1379(84.1) | 0.001 |

| • Clopidogrel | 2126(30.6) | 2897(35.5) | 542(33) | 0.001 |

| • Beta blockers | 3786(54.5) | 3887(47.6) | 594(36.2) | 0.001 |

| • ACE inhibitors/ARBs | 1801(25.9) | 2797(34.3) | 572(34.9) | 0.001 |

| • Thrombolysis therapy | 2690(38.7) | 1945(23.8) | 119(7.3) | 0.001 |

| • GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 309(4.4) | 392(4.8) | 45(2.7) | 0.001 |

| • Unfractionated Heparin | 3044(43.8) | 2870(35.2) | 497(30.3) | 0.001 |

| • LMWH | 1192(17.2) | 1643(20.1) | 335(20.4) | 0.001 |

| Coronary angiography | 1145(16.5) | 824(10.1) | 60(3.7) | 0.001 |

| PCI | 800(11.5) | 859(10.5) | 82(5) | 0.001 |

| CABG | 124(1.8) | 449(5.5) | 120(7.3) | 0.001 |

| LVEF <40% | 439(26.5) | 827(35.6) | 242(33.8) | 0.001 |

| Discharge medications | ||||

| • Aspirin | 6445(92.8) | 7223(88.5) | 1246(76) | 0.001 |

| • Clopidogrel | 2233(32.1) | 2987(36.6) | 541(33) | 0.001 |

| • Beta-Blockers | 2341(33.7) | 2389(29.3) | 402(24.5) | 0.001 |

| • ACE inhibitors/ARBs | 2560(36.9) | 3516(43.1) | 645(39.3) | 0.001 |

| • Statins | 3422(49.3) | 4460(54.7) | 791(48.2) | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: ACE inhibitors,angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors;ARBs,angiotensin-receptor blockers; GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; LVEF, Left ventricular ejection fraction.

In-hospital Outcomes According to Age

| Variables Number (%) | Age ≤50 Years | Age 51-70 Years | Age >70 Years | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure | 137(2) | 394(4.8) | 154(9.4) | 0.001 |

| Shock | 133(1.9) | 247(3.0) | 83(5.1) | 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest | 236(3.4) | 421(5.2) | 182(11.1) | 0.001 |

| Stroke | 14(0.2) | 31(0.4) | 12(0.7) | 0.003 |

| Death | 231(3.3) | 494(6.1) | 237(14.5) | 0.001 |

Trends in the Number of Admissions and In-hospital Mortality Rates Over the 20-years Study Period

| Years | 1991-94 | 1995-98 | 1999-02 | 2003-06 | 2007-10 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | 1775(10.6) | 1836(11) | 2412(14.4) | 4655(27.8) | 6072(36.3) | |

| Age (Mean ±SD, years) | 51.7±12 | 51.7±11.6 | 54.4±12 | 54.9±11.7 | 54.5±11.7 | 0.001 |

| Death (%) | 175(9.9) | 168(9.2) | 213(8.8) | 212(4.6) | 195(3.2) | 0.001 |

| Age ≤50 years | 45 (5.2) | 43 (4.7) | 57 (5.5) | 48 (2.8) | 36 (1.5) | 0.001 |

| Age 51-70 years | 81 (11.1) | 95 (12) | 109 (9.8) | 106 (4.4) | 103 (3.3) | 0.001 |

| Age >70 years | 47 (33.8) | 30 (25.2) | 47 (17.5) | 57 (11.8) | 56 (8.9) | 0.001 |

Multivariable Risk factors for In-Hospital Mortality

| Variables | Adjusted OR | 95% C.I. | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender Male | 0.64 | 0.55 – 0.76 | 0.001 |

| Smoking | 0.67 | 0.57 – 0.80 | 0.001 |

| DM | 1.43 | 1.24 – 1.66 | 0.001 |

| HTN | 0.62 | 0.53 – 0.72 | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.67 | 0.56 – 0.80 | 0.001 |

| Family History of CAD | 0.64 | 0.35 – 1.18 | 0.15 |

| Prior MI | 1.30 | 1.10 – 1.53 | 0.002 |

| Prior PCI | 0.56 | 0.42 – 0.76 | 0.001 |

| Chronic Renal impairment | 1.70 | 1.29 – 2.23 | 0.001 |

| Prior CABG | 0.60 | 0.42 – 0.86 | 0.005 |

| Heart Failure | 2.81 | 2.36 – 3.33 | 0.001 |

| Age 51 – 70 Year | 1.47 | 1.24 – 1.74 | 0.001 |

| Age > 70 Year | 3.09 | 2.51 – 3.82 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension.

The reference is age group ≤ 50 yrs

The mean age of patients was 54 ± 11.9 years (6946 patients were aged ≤50 years, 8158 were between >50 and 70 years and 1640 patients were >70 years old). Women were increasingly represented with increasing age. HTN, DM , renal failure, prior MI and prior coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) were more prevalent among older patients, while the prevalence of current smoking, family history of CAD and prior PCI were highest in the younger age group (P = 0.001). There was no significant difference among the 3 age groups with respect to dyslipidemia. Older patients were more likely to present with non-typical ischemic symptoms including higher frequency of palpitations and dyspnea when compared with the younger age groups. Older patients were more likely to present with non-ST- elevation MI, while younger patients were more likely to present with ST-elevation MI (P = 0.001).

A higher level of mean total cholesterol, serum triglyceride and low-density lipoprotein were more prevalent in patients aged ≤ 70 years. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <40% was more prevalent in the elderly than in patients ≤50 years (34 vs 27%, P = 0.001).

MANAGEMENT (TABLE 2)

On admission, the elderly were less likely to receive evidence-based therapies. The use of aspirin and β-blockers were more prevalent in the younger age group (P = 0.001). Clopidogrel use was higher among the middle-age group when compared with the other 2 groups. Elderly patients with ST-elevation MI were less likely to receive thrombolytic therapy when compared with the younger age groups. Also, with elderly with ACS were less likely than patients ≤ 50 years to undergo coronary angiography (4 vs 17%), to receive glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa inhibitors, and to be treated by PCI (5 vs 12%). However, CABG surgery performance within the same hospitalization increased from 2% among patients ≤50 years to 7% in patients >70 years (P = 0.001 for all). The use of β-blockers was more frequent in men compared with women in age ≤50 (55 vs 48%) and between 51 and 70 years (49 vs 41%), (P = 0.001 for each). The use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (33 vs 25%) was higher in men compared with women in age ≤50 years. However, there was no significant difference in the use of β-blockers and ACE inhibitors in both genders in the other age groups.

The use of unfractionated heparin was more prevalent among patients ≤ 50 years, whereas, the low molecular weight (LMW) heparin was more prevalent among patients >50 years (p = 0.001). Also, ACE inhibitors/angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) use was highest among patients >50 years old (p = 0.001).

On Discharge

Elderly patients were less likely than patients aged ≤50 years to be treated with aspirin (76 vs 93%) and β-blockers (25 vs 34%). On the other hand, patients in the age group 51-70 years were more likely than other age groups to be treated with clopidogrel, ACE inhibitors/ARBs and statins (p = 0.001).

OUTCOME (TABLE 3)

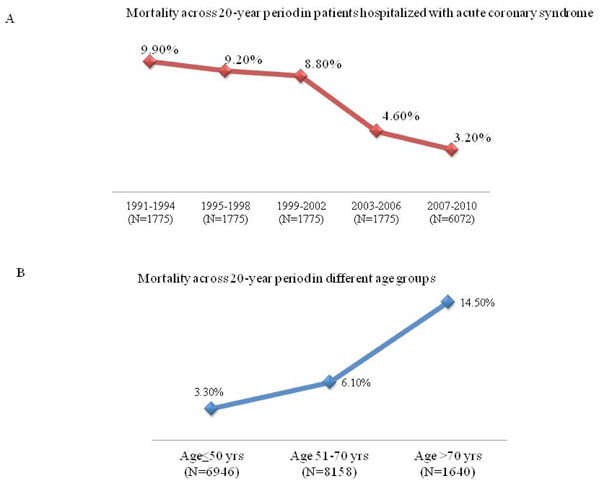

Mortality rates across 20-year period in different age groups are shown in Fig. (2B). Older age ACS patients had significantly higher in-hospital mortality rate, cardiogenic shock, cardiac arrest, heart failure and stroke when compared with the younger age groups (p = 0.001). The mortality rates were higher in women when compared with men in all age groups [7.3 vs 3.1% in age ≤50 (P=0.001), 9% vs 5.4% (P=0.001) in between 51-70, and 17.2 vs 13% in age > 70 years (P=0.03).

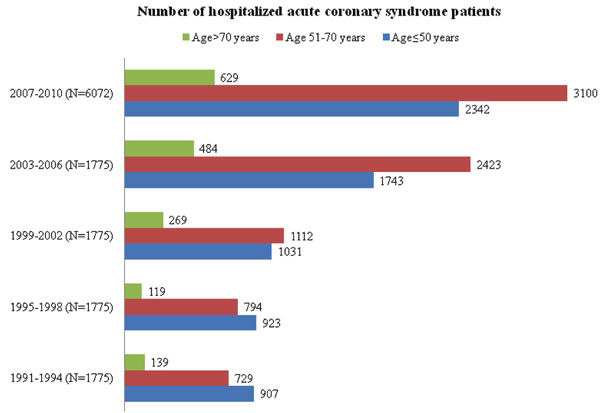

Trends in the number of hospitalization of patients according to age.

Trends in in-hospital mortality rates over the study period.

TREND OF HOSPITALIZATION AND OUTCOME (TABLE 4, FIGS. 1 AND 2)

Over the 20-year period, there was an increase in the total number of patients hospitalized with ACS and was accompanied by higher percentage of older age patients. The overall, in-hospital mortality rates significantly decreased from 9.9 to 3.2%, this decrease in mortality rates occurred regardless of age (Fig. 2A). When the mortality rates for the period 1991 to 2006 were combined and compared with the period of 2007 to 2010, the relative reduction in mortality rates was higher in the younger patients when compared with the older patients (61, 45.9 and 35.5%).

MULTIPLE LOGISTIC REGRESSION ANALYSIS (TABLE 5)

Advancing age (OR 1.47; 95% CI 1.24-1.74 for age 51-70 and OR 3.09; 95%CI 2.51-3.82, for age > 70 years), female gender, DM, chronic renal impairment, heart failure and prior history of MI were independent predictors of death.

DISCUSSION

We showed increased in-hospital mortality in older compared with younger ACS patients. Despite the fact that older ACS patients were a higher risk group when compared with younger patients, they were undertreated with evidence-based therapies. Older age was independent predictor of in-hospital mortality. Furthermore, this decrease in mortality rates was more substantial in the younger age groups. This improvement in outcome may be attributed, at least in part, to increased use of evidence-based therapies.

THE PREVALENCE AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF OLDER AGE PATIENTS

The mean age of the population (54 years) in the present study (1991-2010) is comparable to that reported in the Indian CREATE registry (2005) [10] and Gulf RACE (Registry of Acute Coronary Events) Registry (6- Middle-eastern countries, 2007) [11] and was significantly younger when compared with reports from the 1st and 2nd Euro Heart Surveys (2002 and 2006) [12,13] and GRACE (2003) [3]. Consistent with a previous study [14], the proportion of women increased with increasing age.

The percentage of elderly patients ≥70 years was 21% in the ACCESS (ACute Coronary Events - a multinational Survey of current management Strategies) [15] and 13% in the CREATE registry which were higher than reported in the current study (9.8%). This may be attributed to the fact that similar to other Middle-eastern Gulf countries, the population in Qatar is younger when compared with other parts of the World, with an overall median age of 30.8 years (men; 32.9 years and women; 25.5 years), 2011 estimate (CIA factbook). Consistent with a previous study [14], the clinical characteristics of ACS patients vary according to age. The most prevalent CAD risk factors in the younger patients was current smoking, family history of CAD and prior PCI, whereas history of DM, HTN, renal failure, prior MI and CABG were more common in elderly patients. These variations in risk factor patterns in young and elderly patients highlight the urgent need for international awareness, real effort and national policies for primary and secondary prevention of CAD.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND ACS TYPE

Older ACS patients were less likely to present with typical chest pain than younger patients and this atypical presentation may increase the risk of misdiagnosis and delay diagnosis. In terms of ACS types, as in previous studies [14,16], older patients were more likely to have Non-ST-elevation MI and the proportion of ST-elevation MI decreased with increasing age. In the present study, the frequency of ST-elevation MI constituted two-fifths of our patients compared with one-third in other ACS survey [4,14]. This may be attributed to the relatively younger age group of ACS (54 years), which is almost a decade younger than those reported from developed countries [16].

HOSPITAL MANAGEMENT AND OUTCOMES

Although, CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes With Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines) database [2,17] suggested that advanced patient age (>90 years) should not be a contraindication for early aggressive treatment which was associated with lower rate in-hospital mortality when compared to patients treated with conservative approach, the current study demonstrated the paradox of undertreatment of older patients when compared with the younger age group.

Our data is concordant with other studies [2,16,18,19] showing that older patients were less likely to receive evidence-based ACS medications and coronary angiography than their younger counterparts. It should be noted that there is no age limitation to the use of fibrinolytic therapy among ST-elevation MI patients and prompt reperfusion for patients with ST-elevation MI is a class 1 ACC/AHA guideline recommendation and has been shown to reduce mortality [20]. In the present study, the highest proportion of patients who received thrombolytic therapy was the younger age group. Also, most of elderly patients presenting with ACS were treated conservatively during the same admission with only 3.7% offered coronary angiography and only 5% undergoing PCI. The use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors was very low in all ACS strata, the highest being among the middle-age group when compared with the other 2 groups.

In the GRACE analysis [21], 4 factors were found to be strongly related to lack of reperfusion therapy use among ST-elevation MI patients; age ≥75 years, prior congestive HF, prior MI or prior CABG surgery. Other variables associated with not offering reperfusion were female, diabetes, and delayed presentation [21, 22].

In our study, only a small number of patients underwent CABG surgery during the same admission which occurred mostly in the older group (7.3%) and this is most likely attributed to the fact they were more likely to have more severe and extensive CAD when compared with the younger age. In a prior study [16], the rate of CABG surgery was highest among patients aged 65-74 years (8.1%) when compared with the younger and older age groups.

Prior data reported the long-term benefit of β-blockade use (in elderly patients) and ACE inhibitors use (regardless of age) after ACS [23,24]. The current study showed that the use of evidence-based medical therapies at hospital discharge was less common in the elderly when compared with those ≤ 70 years. The use of β-blockade decreased significantly with increasing age and the use of ACE inhibitors/ARBs, clopidogrel and statins was more prevalent in age group 51-70 years (P = 0.001).

In previous studies [2,14,16], age was found to be an independent predictor of worse in-hospital outcomes after ACS. In the present study, the short-term outcome in older patients was poor, with increased risk of HF, cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest. Also, the in-hospital mortality due to any type of ACS was increased from 3.3-6.1% in patients <70 years of age to 14.5% in patients >70 years of age.

Following adjustment for relevant variables the adjusted odds ratio for in-hospital mortality was 1.59 for patients age 51 - 70 years and 3.65 for those age >70 years. The overall worse prognosis in elderly is multifactorial due to increasing age itself [1,14], high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, atypical presentation of ACS, impaired left ventricular systolic function [25] and the under use of Guideline-recommended medical and interventional therapies [1, 2, 14].

TRENDS

The current study reported significant reduction in mortality over the 20-year period regardless of age; this significant improvement may be attributed to improvement in health care in terms of early diagnosis and more use of evidence-based therapies. Although the overall use was low, further efforts are needed to optimize their use, which may improve outcomes further. The mortality rates in women was significantly higher than in men regardless of age and this increased mortality rates was in part related to the fact that women were less likely to be managed with evidence based therapies [7,26].

LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

Our study is constrained by the limitations inherent in all studies of historical, observational design. Inaccuracies in the diagnosis and coding of ACS in routine data are well recognized and we relied on the accuracy of such data. Temporal changes in referral and coding practices, in diagnostic accuracy, and in awareness of ACS as a diagnostic entity may have influenced our findings. Other study limitations could include missing data or measurement errors, possible confounding by variables not controlled for, as this was an observational and single-center study. Our study focused on in-hospital outcomes and long-term data were not available. There have been some changes in emphasis in treatment options since the data were recorded. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge the current study addresses unique findings of patients hospitalized with ACS conduced in a large population of patients over a longtime period.

CONCLUSIONS

The clinical characteristics of ACS Middle-eastern patients vary considerably with age. Despite being higher-risk group, older patients were undertreated with evidence based therapy and had worse short-term outcome. Guidelines adherence and improvement in hospital care for elderly patients with ACS may potentially reduce morbidity and mortality.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None. The authors are responsible for the content and the writing of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to acknowledge and extend our gratitude to the Medical Research Center, HMC, Doha, Qatar for their support.