All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Weekend Versus Weekday, Morning Versus Evening Admission in Relationship to Mortality in Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients in 6 Middle Eastern Countries: Results from Gulf Race 2 Registry

Abstract

We used prospective cohort data of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) to compare their management on weekdays/mornings with weekends/nights, and the possible impact of this on 1-month and 1-year mortality. Analyses were evaluated using univariate and multivariate statistics. Of the 4,616 patients admitted to hospitals with ACS, 76% were on weekdays. There were no significant differences in 1-month (odds ratio (OR), 0.88; 95% CI: 0.68-1.14) and 1-year mortality (OR, 0.88; 95% CI: 0.70-1.10), respectively, between weekday and weekend admissions. Similarly, there were no significant differences in 1-month (OR, 0.92; 95% CI: 0.73-1.15) and 1-year mortality (OR, 0.98; 95% CI: 0.80-1.20), respectively, between nights and day admissions. In conclusion, apart from lower utilization of angiography (P < .001) at weekends, there were largely no significant discrepancies in the management and care of patients admitted with ACS on weekdays and during morning hours compared with patients admitted on weekends and night hours, and the overall 30-day and 1-year mortality was similar between both the cohorts.

INTRODUCTION

Staffing patterns in hospitals differ on weekdays compared with weekends. In the latter, staffing is reduced numerically and in terms of expertise, to the extent that admissions on weekends have been associated with more adverse outcomes [1]. Further, patients admitted on weekends are less likely to undergo appropriate medical investigations or receive appropriate interventions compared with patients admitted during weekdays [2]. Hospitals with the fewest senior doctors available on weekends have the highest mortality rates [1]. This is often collectively referred to as the “weekend effect”. Delayed treatments and adverse outcomes have also been reported for night admissions compared with morning admissions in various settings including coronary care [2], emergency medical care [3] and intensive care units [4].

Some studies have shown that patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) and heart failure admitted on weekends were at increased risk of mortality compared with similar admissions on weekdays [5-7]. Other studies, however, were less conclusive on the relation of admission day and increased mortality in patients with MI [8-10].

Recruiting medically skilled manpower remains a constant challenge faced by many health care systems in developing countries due to increased competition from industrialized countries and changing global economic scene [11]. Hospitals in the Arab Middle Eastern countries provide standard care during regular working hours of weekdays. On weekends, evening and night hours, only emergency medical services are provided. Presently, there are no studies published from this part of the world regarding weekend and weekday admission disparity among acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients. Therefore, we investigated whether there is a discrepancy in the management and care of patients admitted with ACS on weekdays and during morning hours compared with patients admitted on weekends and night hours. We also assessed the possible impact of such a difference on cumulative mortality (30-day and 1-year post admission) in a large cohort from 6 Middle Eastern countries.

METHODS

Data Sources and Patients

The design and methods of Gulf RACE 2 have been described elsewhere [12]. In summary, the registry was designed as a prospective, multinational, multicentre registry of acute coronary events, focusing on the epidemiology, management practices, and outcomes of patients with ACS. The study recruited consecutive patients aged 18 years and above, from 65 hospitals in 6 adjacent Middle Eastern countries (Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Oman, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen). Data were collected prospectively during the period between October 2008 and June 2009. There were no exclusion criteria. All included hospitals were either secondary or tertiary care hospitals with coronary care units on-site and managed by either general physicians or cardiologists. Patients were followed-up for mortality at 1-month and 1-year through telephone interviews. The diagnosis of the different types of ACS and definitions of data variables were based on the American College of Cardiology (ACC) clinical data standards [13]. As free medical care in some Gulf States is limited to their citizens and excludes non-nationals, we limited our analysis to this cohort with known mortality status at 1-month and 1-year post discharge (n = 4,616 of 7,281 patients).

Study Variables

The primary outcome variables were death at 1-month and 1-year of admission. The primary independent variables were admissions on weekends vs weekdays and morning vs night. Weekend was defined as Thursday and Friday for patients from Saudi Arabia, Yemen and Oman; Friday and Saturday for patients from Bahrain, Qatar and United Arab Emirates. Morning and night admission were defined as admissions during 8.00 am to 7.59 pm and 8.00 pm to 7.59 am, respectively. Covariates included patients’ age, tobacco use, infarction site, medications administered in the first 24 h of admission, presence or absence of co-morbid conditions (diabetes, hypertension, anaemia, chronic renal failure, and cerebrovascular disease), previous history of MI, congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, previous percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), or coronary bypass graft (CABG) and complications during admission. The latter included re-infarct and major bleeding associated with a drop in haemoglobin > 5 g/dL, in addition to 2 composite indexes of mechanical and arrhythmic complications of ACS. The first index included in-hospital complications such as congestive heart failure, mitral regurgitation, ventricular septal rupture and shock (systolic blood pressure ≤90 mmHg or diastolic ≤60 mmHg). The second index was of electrical instability and included non-sinus rhythm, atrial fibrillation, second or third degree block, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation and asystole. The composite indexes stratify 30-day risk of death from ACS as follows: absence of both types of complications, 4.1%; presence of either type of complications, 26%; and presence of both types of complications, 47%. Anaemia was ascertained by admission haemoglobin levels (<13 g/dL for males; <12 g/dL for females).

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages were reported. Differences between groups were analyzed using Pearson’s χ2 tests. For continuous variables, means and standard deviations were used to present the data while analyses were performed using Student t-test. A multiple logistic regression model was used to determine the mortality (1-month and 1-year post admission) difference between patients admitted on weekends and weekdays while accounting for the confounding effects of patient’s demographics and co-morbidity variables. In a similar manner, we also determined if higher mortality was associated with night admission hours (8:00 pm to 07:59 am) compared to regular morning working hours (8.00 am-7:59 pm) admissions. An a priori two-tailed level of significance was set at the 0.05 level. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 12.1 (STATA Corporation, College Station, TX, USA). The study received ethical approval from the institutional ethical bodies in all participating countries.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Patients

Of the 4,616 patients admitted to hospitals with ACS, 76% were on weekdays (Table 1). A similar number of patients with diagnosis of ST-elevation (39 vs 41%; P = .14) and non-ST elevation (32 vs 33%; P = .57) MI were admitted on weekdays and weekends, respectively. There were slightly more admissions with unstable angina on weekdays than weekends (29 vs 26%; P = .02). There were no significant differences between patients admitted on weekdays and those admitted on weekends in terms of age, gender preponderance (72% men), smoking, co-existing morbidities, prior history, anatomical site of MI, medication administered in the first 24 h, rate of in-hospital complications and length of stay in hospital (Table 1). Similar proportion of patients in the weekdays group and weekend group received thrombolytic therapy within the recommended time period (≤30 min) (32 vs 27%; P = .25). Furthermore, recommended door-to-needle time (≤90 min) was not significantly different between the 2 groups (51% in weekdays and 53% in weekends; P = .87). However, PCI (31 vs 26%; P = .006) and CABG (3.2 vs 1.7%; P = .01) were significantly higher in admission on weekdays compared with weekends.

Characteristics of Patients Admitted on Weekdays and Weekends with Acute Coronary Syndrome, Oct 2008 to June 2009, Gulf RACE-2

| Characteristic | Weekdays (n = 3,514) | Weekend (n = 1,102) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age±SD, mean, years | 59.6±12.7 | 59.5±12.0 | 0.71 |

| Males (%) | 72.1 | 72.6 | 0.74 |

| Current smokers (%) | 28.4 | 29.5 | 0.49 |

| Co-existing conditions (%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 41.6 | 41.7 | 0.95 |

| Hypertension | 50.2 | 49.6 | 0.74 |

| Anaemia | 33.3 | 35.3 | 0.22 |

| Renal diseases | 4.9 | 5.8 | 0.26 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 5.1 | 6.4 | 0.08 |

| Prior history of (%) | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 22.6 | 21.4 | 0.39 |

| Congestive heart failure | 8.5 | 7.5 | 0.30 |

| Valvular heart diseases | 2.0 | 1.4 | 0.27 |

| PCI | 10.5 | 9.8 | 0.49 |

| CABG | 4.9 | 4.9 | 0.94 |

| Type of ACS, (%) | |||

| STEMI | 38.9 | 41.4 | 0.14 |

| Non-STEMI | 31.6 | 32.5 | 0.57 |

| Unstable angina | 29.5 | 26.0 | 0.02 |

| Site of STEMI (%) (n=1,718) | |||

| Anterior | 60.2 | 55.8 | |

| Inferior | 37.1 | 40.7 | |

| Lateral | 2.5 | 3.3 | 0.42 |

| Other site | 0.23 | 0.23 | |

| Medication in 1st 24h post admission | |||

| Aspirin | 98.2 | 98.4 | 0.68 |

| Clopidogrel | 71.5 | 71.6 | 0.56 |

| B-blockers | 71.8 | 71.8 | 0.95 |

| ACEI/ARB | 75.7 | 76.9 | 0.45 |

| Statins | 94.0 | 94.4 | 0.67 |

| Heparin | 78.5 | 78.8 | 0.87 |

| In-hospital complications (%) | |||

| Mechanical | 19.3 | 19.9 | 0.69 |

| Arrhythmic | 7.4 | 6.3 | 0.25 |

| Re-infarct | 2.6 | 3.0 | 0.53 |

| Major bleed | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.96 |

| Procedures during admission (%) | |||

| Angiography | 31.0 | 26.6 | 0.006 |

| PCI | 13.9 | 13.6 | 0.82 |

| CABG | 3.2 | 1.7 | 0.01 |

| Length of stay ±SD, mean, days | 6.4 | 6.1 | 0.24 |

| Door-to-needle ≤30 min (%) (n = 739) | 32.1 | 27.7 | 0.25 |

| Door-to-balloon time ≤90 min (%) (n = 121) | 51.6 | 53.3 | 0.87 |

| Mortality, (%) | 10.2 | 9.2 | 0.33 |

| 30-day mortality | 10.2 | 9.2 | 0.33 |

| 1-year mortality | 15.4 | 13.8 | 0.23 |

STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; ACEI/ARB, Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptors blockers; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; SD, Standard deviation.

Association between 1-month Mortality and “Weekend Effect” Adjusting for Demographic and Clinical Variables Among Acute Coronary Syndrome Patients in the Middle East

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weekend | 0.88 | 0.68 | 1.14 |

| Age (yrs) | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.04 |

| Female sex | 1.06 | 0.82 | 1.37 |

| Current smoking | 1.18 | 0.89 | 1.56 |

| Aspirin | 0.77 | 0.40 | 1.48 |

| Clopidogrel | 1.07 | 0.82 | 1.39 |

| Beta-Blockers | 0.66 | 0.52 | 0.83 |

| ACEI/ARB | 0.56 | 0.44 | 0.71 |

| Statins | 0.72 | 0.49 | 1.06 |

| Heparin | 1.33 | 0.99 | 1.79 |

| History of diabetes | 1.05 | 0.83 | 1.34 |

| History of hypertension | 0.70 | 0.54 | 0.89 |

| History of cerebrovascular disease | 1.20 | 0.79 | 1.83 |

| History of congestive heart failure | 0.69 | 0.47 | 1.00 |

| History of valvular heart disease | 1.25 | 0.64 | 2.47 |

| Renal disease | 1.21 | 0.77 | 1.89 |

| Anaemia on admission | 1.28 | 1.02 | 1.61 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1.03 | 0.76 | 1.39 |

| Previous PCI | 0.92 | 0.60 | 1.43 |

| Previous CABG | 0.60 | 0.33 | 1.09 |

| Mechanical complications | 6.73 | 5.27 | 8.60 |

| Arrhythmic complications | 1.79 | 1.29 | 2.47 |

| Length of stay (days) | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.01 |

| In-hospital re-infarct | 1.74 | 1.06 | 2.86 |

| In-hospital major bleeding | 7.08 | 2.99 | 16.76 |

| Angiography | 0.58 | 0.38 | 0.88 |

| PCI | 1.11 | 0.64 | 1.91 |

| CABG | 0.90 | 0.34 | 2.35 |

ACEI/ARB, Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptors blockers; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft

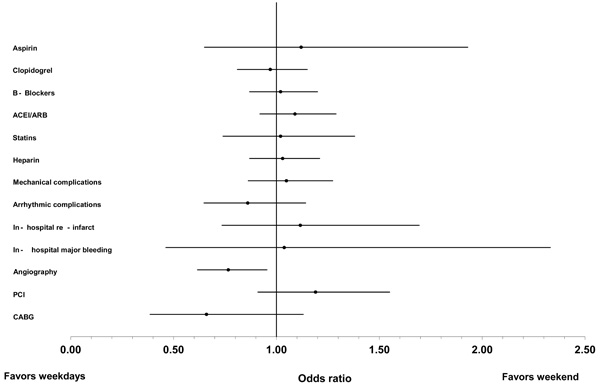

Interventions and Complications During Admission

Fig. (1) shows the adjusted odds ratios of patients admitted on weekends vs weekdays. The results demonstrated that there were generally no significant differences in medications use and in-hospital complications between ACS patients admitted on weekends vs weekdays. However, patients admitted on weekends were less likely to undergo angiography (adjusted odds ratio (OR), 0.77; 95% CI: 0.62-0.95; P < .001) than those admitted on weekdays.

Adjusted odds ratio of provision of medication, interventions and complications in patients on weekend versus weekdays, Gulf RCE 2, Sep 2008-Dec 2009.

Mortality

The overall 1-month mortality for weekday admissions was 10.2% compared with 9.2% for weekend admissions (P = .33), with absolute difference of 1% and relative difference of 10.9%, in favor of weekends over weekdays group (Table 1). Similar differences persisted over the year with 1-year mortality in weekday admissions reaching 15.4% compared with 13.8% in weekend group (P = .23); (absolute difference of 1.6%, relative difference of 11.6%) in favor of the weekend group. After adjusting for demographic characteristics, medications administered in first 24 h of admission, presence or absence of co-morbidities, complications and length of stay, admission during weekends, there were no significant differences in mortality in ACS patients between weekday and weekend admissions (OR, 0.88; 95% CI: 0.68-1.14; P > .05) (Table 2). There were also no significant differences in mortality at 1-year between those ACS patients admitted weekdays vs those admitted at weekends (OR, 0.88; 95% CI: 0.70-1.10; P > .05) (data not shown)

When data was re-analysed using morning vs night hour shifts, a similar pattern to weekends vs weekdays was observed. There were no significant differences in mortality at 1-month (OR, 0.92; 95% CI: 0.73-1.15; P > .05) or 1-year (OR, 0.98; 95% CI: 0.80-1.20; P > .05) in the ACS patients (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis of a cohort from 6 Middle-East countries shows no increase in cumulative mortality risk (at 1-month and 1-year post admission) in patients admitted to hospitals with ACS on weekends compared with those admitted on weekdays, even after adjusting for potential confounders. Similarly, the adjusted odds ratio of mortality of patients admitted on night hours was not worse than those admitted during morning hours. A large study of patients with acute MI, from United States (n = 62,814), also could not show higher in-hospital mortality in weekend and off-hours admissions compared with those presenting during weekdays and regular hours [8] Another study from Switzerland (n = 12,480), after adjusting for several confounding variables, could not demonstrate the “weekend effect” in patients with acute MI, and reported equal survival rates (P = 1.00) for weekday and weekend groups [9]. In a large Japanese registry study, there were no obvious differences in occurrence, hospital admission and acute outcome for acute MI patients in the weekday or weekend [14]. In a study from Italy, there was an increased incidence of ST-elevation MI during weekends and night hours, which was not seen in the current study [15].

In contrast, Kostis and colleagues, investigated 4 cohorts with over 230,000 patients during 1987-2002, for possible “weekend effect” [5]. They reported 4.8% higher mortality rates at 1-month in patients admitted on weekends vs weekdays, which persisted even after adjustment of demographic variables. The magnitude of this increase in mortality however, was reduced to 2.3% and became non-significant (P = .09) once analysis accounted for invasive cardiac procedure. In another study in Germany, higher mortality of 1.7% remained significant despite adjustment for an array of patients’ characteristics and clinical variables [16].

Studies across many disciplines quantified the “weekend effect” in terms of delays in therapeutic or diagnostic procedures and decrease in survival rates, but they failed to precisely outline the mechanisms for this effect [6]. Most commonly, lack of staffing in terms of quantity (total number of clinical staff) and quality (senior specialist and consultants cover) appears to be commonly cited factors related to the weekend and night hours’ phenomenon [17]. In a survey of hospitals in the United Kingdom, only 16% of hospitals provided consultant cover for 9-12 h/day for acute admissions during weekends compared with 49% during weekdays [18]. One of the major reason for the absence of this ‘weekend effect’ could be the presence of senior level staff in the Gulf countries in terms of quantity as well as quality, as majority of the hospitals employ expatriate staff who are at senior level and experienced to work during weekends and after hours. In addition, most hospitals in the Middle-East are well-equipped with medical resources and medications, freely available at hand to provide uniform care during “out of hours” periods [19].

In the present study, we found patients admitted on weekends were less likely to undergo angiography as were those admitted on weekdays. This is similar to a study from the United States of America [5]. Quaas et al. [20] found that patients in Manchester, UK, were 75% less likely to undergo coronary angiography on weekends compared with weekdays. Magid and colleagues, studied 68,439 patients with ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) treated with fibrinolytic therapy and 33,647 treated with PCI, and reported off-hour admissions were associated with substantially longer times to treatment for PCI but not for thrombolytic therapy [2]. Few studies report fewer PCI and significantly longer door-to-balloon time for weekends vs weekdays [21]. However, in the present study, even though coronary angiography was performed less during weekends, there was no significant difference in door-to-needle as well as door-to-balloon times during weekdays and weekends. This suggests that hospital care on weekends and weekdays in the Middle-East may differ in aggressiveness, but not in quality of care. In our previous analysis, due to non-availability of catheterization facilities, the overall utilization of catheterization in ACS patients was low (at 20%) among the Gulf countries [22] and naturally it was even lower during weekends compared with weekdays in this study.

It is also suggested that conditions with increased weekend mortality are those requiring invasive procedures [6]. On the contrary, few authors note that the increased mortality with weekend admissions of patients with some conditions that do not require invasive therapy suggest that the increase in mortality may be due to the decreased weekend availability of cognitive skills and other hospital services rather than to fewer invasive procedures directly [23]. In addition, in a recent Korean study which reported a higher risk of mortality on weekends vs weekdays, medication usage was significantly low during weekends [24]. Even though in the Middle-East overall usage of invasive procedures was low during both weekend and weekdays, we hypothesize that rest of the ACS care including recent evidence-based medication usage was similar during weekdays and weekends along with presence of senior staff leading to no difference in risk of mortality. An alternative explanation for no influence of weekend admission on mortality is that this may be an underestimate because patients admitted on weekends may ‘crossover’ to receive weekday care and vice versa as noted by others [25].

Our study has several limitations. First, the number of patients who received fibrinolysis (n = 739/1718) and PCI (n = 121/1718) was small compared with all those eligible, and the impact of door-to-needle-time and door-to-balloon-time on weekend admissions could not be assessed independently of other confounders, despite both being important factors in patient survival. Secondly, 11.5 and 23% of patients were lost to follow-up at 1 month and 1 year, respectively. Patients who are lost to follow-up are likely to have died but are misclassified as lost to follow-up and thus censored in analysis rather than analyzed as an event. Although this process may underestimate mortality rates, it is unlikely to have affected weekend or weekday admission selectively and thus is unlikely to have favored weekend survival over weekdays. Thirdly, although majority of Middle-East countries employ senior expatriate physicians and nursing staff during weekends and off-hours resulting in the consistent management of ACS patients, we do not have exact information on physician characteristics (e.g. experience, specialty training) and hospital-specific characteristics (e.g. staff volume). A large number of regional hospitals in the region, however, lack on-site catheterization facilities as reported in a recent publication on ACS in the Arabian Middle East [22]. Fourthly, the present study does not account for deaths before hospital admission which may form a significant proportion of total mortality, and thus underestimating the mortality difference. Fifth, this study did not take into account public holidays which were very few and unlikely to have affected the results. Lastly, the number of PCI and CABG procedures performed during weekends was probably too small to show any difference with weekday rates.

Future work should assess whether different characteristics at weekends play a role in influencing the risk of unstable angina. For example, different waking times, size and timing of meals, home vs work stress and increased sport activities.

In conclusion, among the Gulf States, apart from lower utilization of angiography at weekends, there were largely no significant discrepancies in the management and care of patients admitted with ACS on weekdays and during morning hours compared with patients admitted on weekends and night hours, and the overall 30-day and 1-year mortality was similar between both the cohorts. These results indicate that there is a consistent approach to the management and care of ACS patients during weekend and weekdays in the Middle-East countries.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

FUNDING

Gulf RACE is a GHA project supported by Sanofi-Aventis, Paris, France and College of Medicine Research Center at King Khalid University Hospital, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The sponsors had no involvement in the study conception or design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; writing, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all patients who consented to this study as well as all physicians who collaborated in the data collection and data management. Thanks also go to Zenaida Ramoso and Kazi Nur Asfina for their data coordination and administrative assistance. Finally, this project would not have been possible if it were not for the special leadership and support of Dr Hajar Albinali, President of Gulf Heart Association (GHA).