All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Relationship Between MMP-1, MMP-9, TIMP-1, IL-6 and Risk Factors, Clinical Presentation, Extent and Severity of Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease

Abstract

Background:

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and Tissue Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinases (TIMPs) may be associated with atherogenesis and plaque rupture. We evaluated the relationship between MMP-1, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and IL-6 levels and risk factors, presentation, extent and severity of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD).

Methods:

Consecutive patients who underwent coronary angiography were randomly included. The serum concentrations of MMP-1, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and IL-6 were analyzed with ELISA method in 134 patients. Participants were divided into 5 groups; stable angina pectoris (SAP; n= 34), unstable angina pectoris (USAP; n=29), non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI; n=16), acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI; n=25) and controls (n=30). Coronary angiographic Gensini score was calculated.

Results:

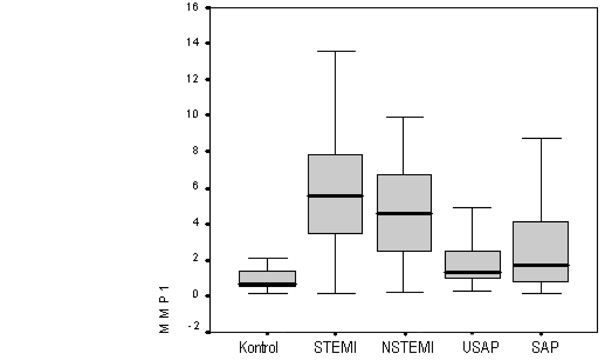

MMP-1 levels were higher in STEMI and NSTEMI groups compared with USAP, SAP and control groups (STEMI vs USAP p=0.005; STEMI vs SAP p=0.001; STEMI vs control p<0.001; NSTEMI vs USAP p=0.02; NSTEMI vs SAP p=0.027; NSTEMI vs control p<0.001). In STEMI group, MMP-9 levels were higher than USAP and control groups (p=0.002; p<0,001). TIMP-1 levels were not significantly different within all 5 groups. MMP-1 levels were found to be elevated in diabetic patients (p=0.020); whereas MMP-9 levels were higher in smokers (p=0.043). Higher MMP-1, MMP-9 and IL-6 levels were correlated with severe Left Anterior Descending artery (LAD) stenosis and higher angiographic Gensini Score (for severe LAD stenosis; r = 0.671, 0.363, 0.509 p<0.001; for Gensini score; r = 0.717, 0.371, 0.578 p<0.001).

Conclusions:

Serum levels of MMP-1, MMP-9, and IL-6 are elevated in patients with CAD; more so in acute coronary syndromes. MMP-1, MMP-9 and IL-6 are associated with more extensive and severe CAD (as represented by Gensini score).

INTRODUCTION

Atheroma is no longer considered simply as lipid deposition on the coronary artery wall. Inflammation, rather than the severity of narrowing of the arterial lumen plays the pivotal role for thrombotic complications in coronary artery disease (CAD) [1].

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) which are secreted mostly by inflammatory cells are members of a zinc-dependant enzyme family which degrades extracellular matrix [2]. The disturbance of the physiologic balance between extracellular matrix production and degradation results in atherosclerosis in the cardiovascular system, stenosis in the coronary arteries, left ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure [3]. At least 23 structurally similar MMPs are defined. Although some MMPs are thought to have different effects on atherosclerotic plaque stability, the effect for most MMPs, is the rupture of the coronary plaque by degrading the vascular extracellular matrix components. Global MMP activity is increased in highly inflammatory plaques [4]. It is also reported that the levels of MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-8 and MMP-9 are increased in atheromatous, vulnerable plaques compared with fibrous plaques [1,5]. Angiogenesis which is well known to destabilize the plaque is also stimulated by MMPs [6].

However, some MMPs have a less known effect which is to increase plaque stability by stimulating the migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells from tunica media into tunica intima; thereby increasing the thickness of the atheromatous plaque [7]. MMP-2, MMP-9 and MMP-14 degrades the basal membrane around the vascular smooth muscle cells and render these cells in contact with extracellular matrix. This interaction converts quiescent vascular smooth muscle cells into a proliferative and migratory form. The accumulation of vascular smooth muscle cells in the intima layer of the arterial wall is thought to stabilize plaques by increasing the thickness of the fibrous cap [8].

Results of the clinical studies about the levels of certain MMPs in stable and unstable coronary syndromes are inconsistent, especially for MMP-9.

Our aim was to investigate the serum levels of some selected MMPs in different coronary clinical presentations, in addition to identifying possible use of these molecules as predictors of CAD, severity and extent in stable and unstable cardiac disease. Therefore, we assessed the probable association between the serum levels of MMP-1, MMP-9, TIMP-1, IL-6 and Gensini score, an objective scoring system used to evaluate the extent and severity of CAD.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

140 patients who admitted to the Cardiology Department of our university hospital between January and May 2009 with stable angina pectoris or acute coronary syndromes, and who were decided to undergo coronary angiography were consecutively included. The study was approved by the local Ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to participation. The study was completed with 134 patients due to the inadequate coronary angiographic view or unwillingness of the patient to participate. Since it would be unethical to perform coronary angiography for healthy individuals, the control group of the study consisted of the patients who were found to have normal coronary arteries within the study population.

Patients were divided into 4 groups. Group 1: Acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (n = 25); Group 2: Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) (n = 16); Group 3: Unstable angina pectoris (USAP) (n = 29); Group 4: Stable angina pectoris (SAP) (n = 34); Control group: patients who had normal coronary arteries (n = 30). For the patients with unstable CAD (STEMI, NSTEMI, USAP), it was mandatory to undergo coronary angiography within the first 48 h of admission for inclusion. Exclusion criteria consisted of previous revascularisation, coronary angiography after 48 h of hospital admission for patients with acute coronary syndromes, severe valvular disease, severe renal dysfunction (known renal failure and/or serum creatinin levels >1.6 mg/dL), severe hepatic dysfunction (known cirrhosis and or serum levels of AST, ALT, GGT > 3 times of upper level), severe thyroid disease (increase or decrease in the levels of fT3, fT4 or TSH), malignant disorder (except for cured malignancies).

Demographic parameters, risk factors for atherosclerosis and past medical history were recorded for every participant. Blood samples were obtained for complete blood count, biochemistry/lipid parameters, and pro-Brain Natriuretic Peptide (pro-BNP) levels at admission. Electrocardiographic findings of all patients were recorded and every patient had an echocardiographic examination within 24 h of admission. Serum levels of creatine kinase (CK), creatine kinase myocardial isoenzyme (CKMB) and troponin T were recorded at the 72 nd hour of admission for patients who presented with acute coronary syndromes. Blood for MMP-1, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and IL-6 was obtained through the femoral sheath which was placed into the femoral artery at the beginning of the coronary angiography procedure, centrifuged and kept at -70˚C thereafter. An ELISA (BenderMed System, Vienna, Austria) assay was used for the analysis of MMP and IL levels. Coronary angiography was performed using TOSHIBA Infinix CSI, and 6F catheters for all patients. Presence or absence of Left Anterior Descending coronary artery (LAD) disease with more than 70% stenosis and Gensini score for the extent and severity of coronary atherosclerosis were recorded for each patient.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS for Windows 11.5 was used for the analysis of the data. Shapiro Wilk test was used to determine if the continuous variables were distributed close to normal. Descriptive statistics were shown as mean ± standart deviation or as medians for continuous variables; and as percentage of cases for categoric variables.

One-way ANOVA was used for evaluation of the significance of the difference between the groups in terms of means. Mann Whitney U test was used to evaluate the significance of difference between the groups in terms of medians when the number of groups was two; and Kruskal Wallis analysis was used when the number of groups was more than two. Categorical variables were evaluated by using Pearson’s Ki-square or Fischer’s exact ki-square test. Spearmen’s correlation test was used for the relationship between continuous variables. ROC analysis was used for the determination of the possible use of the markers for clinical differentiation between the case and the control groups. When the area under the curve was found to be significant, the cut-off values were determined and sensitivity and specificity for that particular cut-off point was calculated as well.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the patients are provided in Table 1. There were no differences between the groups in terms of height, weight, body mass index, history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, family history for CAD, smoking habits or basal Hb levels. There was male predominance in the STEMI patients; whereas the percentage of females was higher in the SAP group. Number of diabetic patients were highest in the SAP group, followed by NSTEMI patients. Ischemic electrocardiographic findings were most frequent as expected in the STEMI group; and the ejection fractions of the patients in the STEMI and NSTEMI groups were lower than the others. Table 2 shows the mean serum levels of MMP-1, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and IL-6 in all 4 patient groups and the controls. Number of patients who had metabolic syndrome were different among patient groups (Table 1); but no difference was observed in the marker levels with respect to the presence or absence of metabolic syndrome.

Baseline Characteristics of the Study Population

| Control N:30 | STEMI N:25 | NSTEMI N:16 | USAP N:29 | SAP N:34 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 54.4±12.5 | 58.4±9.8 | 68.1±12.1 | 59.7±10.8 | 63.7±9.4 | <0.001* |

| Gender (F/M) | 17/13(56%) | 5/20(20%) | 9/7(56%) | 9/20(31%) | 14/20(41%) | 0.017** |

| Weight | 77.9±12.5 | 79.5±10.5 | 75.3±12.7 | 79.2±10.7 | 85.1±13.6 | 0.058 |

| Height | 163.3±9.2 | 167.4±8.1 | 162.2±7.5 | 166.5±8.6 | 165.6±9.8 | 0.262 |

| BMI | 29.4±5.2 | 28.4±3.4 | 28.7±5.2 | 28.6±4.1 | 31.2±5.7 | 0.146 |

| Met S | 12 (40.0%) | 13 (52.0%) | 11 (68.8%) | 13 (44.8%) | 26 (76.5%) | 0.021*** |

| HT | 16 (53.3%) | 10 (40.0%) | 11 (68.8%) | 13 (44.8%) | 25 (73.5%) | 0.051 |

| DM | 6 (20.0%) | 8 (32.0%) | 6 (37.5%) | 6 (20.7%) | 17 (50.0%) | 0.062 |

| Glu (mg/dL) | 92(78-300) | 126(80-270) | 130(80-300) | 96(58-161) | 115(63-280) | <0.001† |

| FH | 10 (33.3%) | 11 (44.0%) | 6 (37.5%) | 9 (31.0%) | 7 (20.6%) | 0.414 |

| HPL | 14 (46.7%) | 11 (44.4%) | 8 (50.0%) | 13 (44.8%) | 21 (61.8%) | 0.612 |

| Smoking | 10 (33.3%) | 16 (64.0%) | 7 (43.8%) | 16 (55.2%) | 14 (41.2%) | 0.167 |

| EF (%) | 67 (30-74) | 42.5 (35-57) | 47.5 (28-68) | 66 (20-70) | 66 (45-71) | <0.001†† |

| Hb (g/dL) | 14.1±1.1 | 14.2±1.6 | 13.5±1.9 | 14.2±1.8 | 14.2±1.2 | 0.487 |

| Ischemic ECG | 7 (23%) | 25 (100%) | 8 (50%) | 13 (44.8%) | 6 (17.6%) | <0.001‡ |

Basal characteristics of the study population. BMI: body mass index, Met S: metabolic syndrome, DM: diabetes mellitus, HT: hypertension, FH: family history of atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, EF: ejection fraction, Hb: hemoglobin, Glu: fasting blood glucose. For p values

* control-Non ST Elevation MI (NSTEMI)

** ST Elevation MI (STEMI) - NSTEMI

*** control-Stable Angina Pectoris (SAP)

† control-STEMI/NSTEMI

†† control-STEMI/NSTEMI

‡ control-STEMI/NSTEMI.

Levels of Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), Tissue Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and Interleukin-6 (IL-6) in Different Clinical Groups

| Marker | Clinic | N | Mean | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| MMP-1 (ng/ml) | control | 30 | 0.989 | 0.10 | 4.08 |

| STEMI | 25 | 5.8232 | 0.08 | 13.60 | |

| NSTEMI | 16 | 4.6969 | 0.21 | 9.89 | |

| USAP | 29 | 2.3224 | 0.28 | 11.87 | |

| SAP | 34 | 2.8668 | 0.11 | 14.73 | |

| Total | 134 | 3.0987 | 0.08 | 14.73 | |

|

|

|||||

| MMP-9 | control | 30 | 175.16 | 52.0 | 431.0 |

| (ng/ml) | STEMI | 25 | 454.36 | 58.0 | 1500.0 |

| NSTEMI | 16 | 284.43 | 52.0 | 1008.0 | |

| USAP | 29 | 209.93 | 31.0 | 537.0 | |

| SAP | 34 | 291.67 | 52.0 | 1261.0 | |

| Total | 134 | 277.38 | 31.0 | 1500.0 | |

|

|

|||||

| IL-6 | control | 30 | 1.81 | 1.55 | 2.88 |

| (pg/ml) | STEMI | 25 | 2.74 | 1.55 | 6.06 |

| NSTEMI | 16 | 2.96 | 1.64 | 6.93 | |

| USAP | 29 | 2.19 | 1.55 | 6.86 | |

| SAP | 34 | 2.13 | 1.55 | 7.01 | |

| Total | 134 | 2.28 | 1.55 | 7.01 | |

|

|

|||||

| TIMP-1 | control | 30 | 527.79 | 177.20 | 953.00 |

| (ng/ml) | STEMI | 25 | 466.68 | 65.20 | 768.50 |

| NSTEMI | 16 | 478.88 | 44.0 | 720.70 | |

| USAP | 29 | 516.69 | 110.5 | 1212.80 | |

| SAP | 34 | 551.69 | 111.10 | 1280.00 | |

| Total | 134 | 514.21 | 44.0 | 1280.00 | |

Cut-off Values for Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), Interleukin-6 (IL-6); for Coronary Artery Disease

| Cut-Off | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP-1 (ng/ml) | >2.03 | 57 | 93 |

| MMP-9 (ng/ml) | >158 | 72 | 63 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | >1.97 | 46 | 86 |

Correlation Coefficients of Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and Interleukin- 6 (IL-6) with Gensini Score and >70% LAD Stenosis

| Gensini Score | >70% LAD Stenosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Coefficient | P | Correlation Coefficient | p | |

| MMP-1 | 0.717 | <0.001 | 0.671 | <0.001 |

| MMP-9 | 0.371 | <0.001 | 0.363 | <0.001 |

| IL-6 | 0.578 | <0.001 | 0.509 | <0.001 |

MMP-1

MMP-1 levels were significantly higher in all coronary artery disease patients compared with the control group; and the patients who presented with STEMI or NSTEMI had higher levels of MMP-1 compared to USAP and SAP patients (STEMI vs USAP p = 0.005; STEMI vs SAP p = 0.001; STEMI vs control p<0.001; NSTEMI vs USAP p = 0.02; NSTEMI vs SAP p = 0.027; NSTEMI vs control p<0.001) (Fig. 1). Hypertensive status, family history of CAD and hyperlipidemia had no effect on the levels of the mentioned markers. Diabetic patients had significantly (p = 0.02) higher levels of MMP-1. The mean MMP-1 level was 2.79 ng/mL in non-diabetic patients (n = 91) and 3.75 ng/mL in the diabetic patients (n = 43).

Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) levels according to patient groups.

MMP-9

MMP-9 levels were highest in STEMI patients and this difference was significant when STEMI patients were compared with USAP and control group (p = 0.002; p<0.001). MMP-9 levels were higher in the smokers compared with non-smokers (p = 0.04). The mean MMP-9 level was 245.7 ng/mL in non-smokers (n = 71) and 313.1 ng/mL in smokers (n = 63).

TIMP-1

TIMP-1 levels did not differ significantly but there was a trend towards lower values in the patients who had experienced myocardial infarction.

IL-6

IL-6 levels were significantly different between groups as well (p<0.001). When compared with the control group, all patient groups except for the SAP patients had higher IL-6 levels. In addition, when patient groups were compared within each other, STEMI and NSTEMI patients had significantly higher IL-6 levels than SAP group (p = 0.002; p = 0.005).

Prediction of Coronary Artery Disease and İnterrelations with other Biomarkers

Cut-off values for having CAD were calculated free from the presentation conditions. Table 3 shows the cut-off values, sensitivities and specificities of MMP-1, MMP-9 and IL-6 as predictors of CAD.

The serum levels of MMP-1, MMP-9, TIMP-1 and IL-6 did not correlate with the levels of CK, CKMB or troponin T which were sampled at 72 h of admission in the STEMI and NSTEMI patients.

The pro-BNP levels were higher in STEMI and NSTEMI patients compared with USAP and SAP groups (STEMI vs USAP p = 0.011; STEMI vs SAP p = 0.002; NSTEMI vs USAP p<0.001; NSTEMI vs SAP p<0.001). There was a weak but significant correlation between pro-BNP and MMP-1 levels (correlation coefficient: 0.37; p<0.001) which continued to exist after statistical correction (ejection fraction, age and hypertension) had been conducted for the patient group, (B = 0.11 %95 CI:0.17-0.20).

Extent and Severity of Coronary Artery Disease

There was a significant positive correlation between MMP-1, MMP-9 and IL-6 levels and the Gensini score; whereas such a correlation was not shown for TIMP-1. Patients who had severe stenosis in the LAD also had higher levels of MMP-1, MMP-9 and IL-6. Table 4 shows the correlation coefficients for each of the markers that have been shown to be related with Gensini score and the presence of severe LAD disease.

When statistical regression analysis was conducted to reveal any potential confounding effect of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia and the admission diagnosis of the patient on Gensini score or presence of severe LAD stenosis; the significant relation between MMP-1 and IL-6 were found to persist (For Gensini score B = 0.124 %95 CI: 0.75-0.174; B = 0.217 %95 CI:0.089-0.346; for severe LAD disease B = 0.059 %95 CI:0.031-0.086; B = 0.097 %95 CI:0.025-0.169).

DISCUSSION

We found that MMP-1 levels were higher in the patients with CAD compared with the patients with normal coronary arteries on coronary angiography. In addition MMP-1 levels were elevated to a higher degree in the subgroup of patients who presented with acute coronary syndromes and high serum troponin. Similarly, MMP-9 levels were highest in the STEMI patients. The degree of elevation of MMP-1 and MMP-9 levels before coronary angiography correlated with the clinical condition that the patients presented with. Our findings are in concordance with the results of some histological studies [1,5] which reported that MMP-1, MMP-9, MMP-3 and MMP-8 levels were higher in unstable, vulnerable plaques compared with fibrous, stable plaques; and a clinical study which reported higher MMP-9 levels in the blood sample taken from culprit coronary vessel of STEMI patients compared with blood samples from peripheral vessels of the same patients [9].

Inflammation has been accepted to play a role at all stages of atherosclerotic CAD including rupture of the plaque [10]. Our findings about serum IL-6 levels were concordant with some studies reporting IL-6 elevation in acute coronary syndromes. What we add is that; MMP-1 and MMP-9 were elevated in the same patient groups as IL-6.

TIMP-1, as a tissue inhibitor of MMPs, was expected to be lower in acute coronary syndromes. However, the results did not reach statistical significance but there was a trend towards lower TIMP-1 levels in STEMI and NSTEMI patients.

We provide potential cut-off values for CAD. Although the sensitivities are not so good; the specificities of these molecules as predictors of CAD are better (Sensitivities for MMP-1, MMP-9, IL-6 were 57%, 72%, 46%; specificities were 93%, 63%, 86% respectively). We conclude that MMP-1, MMP-9 and IL-6 levels alone or in combination may prove useful to exclude CAD.

Smoking which is a strong risk factor for CAD by causing endothelial dysfunction, propensity for thrombosis and vasoconstriction [11], was associated with higher blood MMP-9 levels. MMP-9 is a MMP which acts not only in the plaque rupture stage but also in the initial stages where vascular smooth muscle migration to intima and proliferation takes place [12]. Depending on the the stage of atherosclerosis and the activity of other MMPs in the plaque, MMP-9 is thought to be capable of increasing plaque stability by increasing the thickness of the fibrous plaque instead of causing instability [13]. Percentage of smokers in different clinical groups were not significantly different in the entire study population; and MMP-9 which has dual role in atherosclerosis were found to be elevated in the smoker study population regardless of the clinical presentation.

Diabetes is an equivalent of CAD and MMP-1 levels were found to be significantly higher in the diabetic subgroup. We were not able to analyze if the relationship we have reported between these MMPs, diabetes and smoking considering the entire study population also existed when only the control group was analyzed because of the small number of patients for such a statistical analysis.

Considering the success of these markers to predict unstable cardiac disease, we aimed to evaluate the extent of myocardial damage in STEMI or NSTEMI, but we failed to demonstrate a correlation between MMP-1 or MMP-9 with CK, CKMB and troponin T. A possible explanation could be the difference between the timing of blood sampling, which was the 72 nd hour of hospital admission for CK, CKMB and troponin T; and the beginning of the coronary angiography procedure for MMP-1, MMP-9 and IL-6. Although STEMI patients were immediately taken to the catheterisation laboratory and NSTEMI patients had undergone coronary angiography within 48 h of hospital admission, it was impossible to obtain the blood samples exactly at the same time from the beginning of the chest pain for each participant. After a while, MMPs are known to be released from the ischemic myocardium [14]. In addition, in the presence of ongoing inflammatory activity, peripheral monocytes may also serve as sources for MMPs [15]. Last but not least, enzyme levels may not reflect enzyme activity. Considering all of these factors, the lack of correlation between MMPs and cardiac enzymes may be due to a technical inability to reveal a probable relation.

Pro-BNP, a natriuretic peptide used for the diagnosis of heart failure, is stimulated by the tension and stretch of cardiac walls [16,17]. During acute ischemic insult, it is mainly thought to be elevated due to ischemic myocardial wall strech [18]. Currently, human atherosclerotic plaques are also thought to express natriuretic peptides, and there are studies reporting pro-BNP elevation during acute coronary syndromes or percutaneous interventions [19]. As anticipated, we found that pro-BNP levels were higher in the STEMI or NSTEMI patients; and more importantly we were able to show a positive correlation between MMP-1 and pro-BNP although weak. It is meaningful for MMP-1 to have positive relation with pro-BNP which is a widely used marker to indicate a worse clinical condition.

As previously mentioned, MMPs are also released from the infarcted myocardium after STEMI since they are responsible from left ventricular remodelling [20]. In some animal studies; MMP-2, MMP-3 and MMP-9 expression was identified around the infarcted tissue after myocardial infarction [21]. In another study, MMP levels were analyzed after STEMI on day 0, 7, 2nd week and at fourth week; and any relation between MMP levels and ejection fraction was investigated. At day 0, MMP levels were higher in STEMI patients compared with stable angina patients who were chosen as controls and the blood levels of MMP-1 tended to increase until the second week, where it peaked, then decreased. The patients with highest 2nd week and 4th week MMP-1 levels had lower ejection fraction values measured by echocardiography at the 4th week [22].

Our study may be critisized because higher MMP levels were expected in the low EF group; and the relationship between MMP-1 and pro-BNP reflected heart failure. But as we described in the method section; the blood samples were drawn immediately after hospital admission in the STEMI group and within 48 h in the NSTEMI group which means there was not enough time for ventricular remodelling. Since the blood samples were obtained quite early for all patients, MMP levels reflect plaque rupture, not ventricular remodelling or heart failure. In addition, the positive relation between MMP-1 and pro-BNP have continued to exist after statistical correction by regression analysis for ejection fraction were conducted.

There are a few studies which report the relation between MMP-1 levels and 2 or 3 vessel disease or complex coronary lesions [23]. We show that MMP-1, MMP-9, and IL-6 correlated with severe LAD stenosis. In addition we reported that MMP-1, MMP-9 and IL-6 were correlated with Gensini score which provides an objective estimation for the extent and severity of CAD. The relation have persisted for MMP-1 and IL-6 after correction for probable confounders. As far as we know, this is the first study which relates Gensini score with any of MMPs. This relation is promising in predicting the extent and severity of CAD.

The major limitation was the timing of blood sampling. We tried to overcome this problem by including only the patients who were taken to catheter laboratory for coronary angiography within 48 h of hospital admission and excluding those patients whose coronary angiography was delayed for more than 48 h as described in the method section. Still, it is practically impossible to fix the time of blood sampling for NSTEMI and USAP patients, since the time between the onset of the chest pain and hospital admission may differ.

In conclusion; blood levels of MMP-1, MMP-9, IL-6 were elevated in patients with CAD; this elevation was more pronounced in acute coronary syndromes. Most strikingly, they correlated with higher angiographic Gensini score. These findings should encourage future research about using MMPs to predict presence, severity and extent of CAD. Larger studies combining objective coronary angiographic parameters and histologic findings may be suggestive of widespread use of MMPs as risk predictors.

SOURCE OF SUPPORT

The ELISA Assays used for the measurement of blood levels of the markers in this study are afforded by Biofarma Pharmaceutical Company.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Special thanks to Biofarma Pharmaceutical Company for the financial support for providing the ELISA assays used in this study.