All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Behçet’s Disease: an Insight from a Cardiologist’s Point of View

Abstract

Behçet's disease (BD) is an enigmatic inflammatory disorder, with vasculitis (perivasculitis) underlying pathophysiology of its multisystemic affections. Venous pathology and thrombotic complications are hallmarks of BD. However, it has been increasingly recognized that cardiac involvement and arterial complications (aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms, rupture and thrombosis) are important part of the course of BD. Pericarditis, myocardial (diastolic and/or systolic dysfunction), valvular and coronary (thrombosis, aneurysms, rupture) involvement, intracardiac thrombi (predominantly right-sided) are, probably, the most frequent cardiac manifestations. Treatment of cardiovascular involvement in BD is largely empirical and aimed at suppression of vasculitis. The most challenging seems to be the treatment of arterial aneurysms and thromboses due to the associated risk of bleedings. Cardiologists should always bear in mind potential threats of (a)symptomatic cardiovascular involvement in BD.

INTRODUCTION

Over the past decade, pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease has been substantially revised and enriched with new facts and mechanisms of atherothrombogenesis associated with inflammation and immune disorders. Based on the recent numerous experimental and clinical studies, the concept of premature cardiovascular disease has been formulated, which paved ways for more efficacious preventive strategies [1]. It has also become obvious that further investigation of cardiovascular involvement in inflammatory disorders, particularly with persistent low-grade inflammation, would be instrumental for better understanding of the accelerated course of atherothrombotic diseases and adverse vascular events in subjects at a relatively young age [2]. In this regard, it is of great importance to analyze facts of cardiovascular involvement in Behçet’s disease (BD), to consider it as a prime example of thrombotic disease associated with T-cell mediated neutrophilic inflammation, and to outline features of thrombosis, distinguishing BD from other inflammatory disorders.

Notably, the issue of cardiovascular involvement in BD, which was thought to be relatively rare manifestation of the disease, has attracted much attention of cardiologists over the past few decades, owing to the wide-spread use of highly informative diagnostic techniques, such as echocardiography, Doppler cardiography, angiography, computed tomography. As a result, staggering amount of reports, indicating both symptomatic and asymptomatic involvement of different structures of the heart and all types of vessels with predominantly right-sided heart disease and venous thrombotic pathology, has been published [3-11].

The aim of the current communication is to outline the issue of cardiovascular involvement in BD and present some rare cases of interest for cardiologists.

HISTORY AND CLASSIFICATION

BD is a chronic inflammatory disorder with multisystemic manifestations. It is believed that primary descriptions of symptoms resembling BD can be found in the works of Hippocrates [12] and ancient scholars of traditional Chinese medicine [13]. Originally, the disease described by Hulûsi Behçet as a triad of recurrent oral and genital aphthous ulcerations and iritis in 1937 [14]. However, there were also earlier scientific reports of a case of relapsing iritis, hypopyon, leg ulcerations and thrombophlebitis by Benediktos Adamantiades in 1930-1931 [15, 16], who, later on, published two more similar cases, described thrombophlebitis as the forth symptom, and classified the constellation of symptoms as a nosological entity [16]. This is why some authors proposed the term ‘Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease’ to pay tribute to the doctors, who equally contributed to the description of the disease. There was also suggestion to use the term ‘silk route disease’ to stress out geographic origin and primary spreading of BD through the ancient ‘silk route’ [17, 18]. Thorough investigation of clinical, immunological and genetic features of BD led to its classification within the frames of systemic vasculitides, seronegative spondyloarthritides and, more recently, autoinflammatory disorders [19, 20].

Autoinflammatory disorders are heteregenous inflammatory diseases, such as familial Mediterranean fever (FMF), Crohn’s disease, gout, sharing some common features of inflammation and clinical manifestations. Etiology and pathophysiology of these disorders still remain obscure. To date, no specific etiological agents, antibodies or antigen specific immune cells responsible for inflammatory attacks or persistent subclinical inflammation in these disorders have been identified. FMF is one of the most common autoinflammatory disorders, sharing several important features with BD (e.g., frequent detection of mutations encoding pyrin protein, periodic inflammatory attacks with neutrophils as target cells, good response to colchicine) [21]. Importantly, the latest classification of BD within the autoinflammatory disorders may provide clues for better understanding of factors involved in vascular pathology in this disease. At least, it was found out that patients with BD carrying Mediterranean Fever (MEFV) mutations are prone to vascular pathology [22], which is, probably, suggestive of the importance of neutrophilic reactions and potential therapeutic implications of colchicine in vascular pathology in BD. It would be also worth studying features of atherosclerotic disease within the autoinflammatory disorders. Interestingly, evidence derived from observational studies with carotid intimal-medial thickness suggests that BD patients are not prone to atherosclerotic disease [23], whereas the same evidence in FMF suggests the opposite [24]. Better understanding of the differences in atherogenesis and in predominant vascular lesions in BD and FMF could further elucidate mechanisms of inflammation associated vascular pathology.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

While etiology of BD remains unknown, ethnic background, gender-related factors, HLA markers, T-lymphocytes dysfunction, circulating immune complexes, genetically predisposed inflammation and hypercoagulation are thought to be intimately involved in pathophysiology of BD [25, 26].

BD is common in countries along the ancient Silk Route (from the Far East to the Mediterranean region). Turkey, Japan, Korea, China, Iran, Saudi Arabia are among the countries with a high prevalence of the disease (13.5-370 per 100,000 population) [26]. In Western countries estimates of prevalence are much lower (0.12-5.2 per 100,000 populations) [27]. In Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries BD is more common among the middle-aged males, who suffer from more aggressive course of the disease than females [28].

Of diverse HLA markers, only HLA-B51 allele was found to be strongly associated with BD, and it is quite common in patients from countries along the Silk Route (up to 81%) [26]. It is, however, believed that not only genetic markers but also environmental factors may influence the expression and course of the disease. In fact, expression of BD among Turks from Turkey, Germany and USA sharing the same genotype differs, with substantially higher prevalence of the disease in Turkey [29]; the same tendency was noted among Japanese subjects from different countries [30]. Additionally, expression of heat shock protein 60, non-infectious and Th1-meditated neutrophilic activation, immune reactions triggered by Streptococcus sanguis and Herpes simplex virus are frequently considered as links in the pathophysiological chain of BD [31].

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Owing to the lack of specific clinical and laboratory diagnostic tests, several sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed over the past decades. Of these, criteria by the BD Committee of Japan (1987, revised in 2003) [31] and International Study Group for BD (1990) [32] are relatively well validated and in the use worldwide. Based on the International Study Group for BD criteria, the diagnosis requires presence of recurrent oral ulceration plus at least two other criteria (recurrent genital ulceration, ocular signs, skin lesions, positive pathergy test). This set is simpler. Japanese set includes major (oral ulcers, skin lesions, including subcutaneous thrombophlebitis and cutaneous hypersensitivity, eye lesions, genital ulcers or scars) and minor criteria (arthritis, gastrointestinal lesions, epididymitis, vascular lesions, central nervous system complications). For the definite diagnosis presence of four major criteria is mandatory. Both sets lack in the appreciation of the importance of a variety of venous and arterial lesions, and thromboembolic complications, frequently reported as part of initial, oligosymptomatic or classical, overt clinical presentation of BD.

Diagnostic uncertainties also include the issue of cardiac involvement. Perhaps, the diagnosis of cardio-BD in the young subjects originating from countries along the Silk Route should be considered even in cases when major (classical) criteria, such as oral ulcerations or positive pathergy test, are absent. In these cases, detailed analysis of the heart and large vessels structures and functions by echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), CT, and a proper follow-up will be required.

CARDIOVASCULAR INVOLVEMENT

The morphological basis of systemic manifestations in BD, including cardiovascular involvement, is vasculitis [33]. More specifically, some pathologists consider perivascular structures as the main target of T-lymphocytes mediated immune reactions and ‘perivasculitis’ as an essential part of vasculopathy in BD [34, 35]. Importantly, vasculopathy in BD is not associated with anti-Ro, antiphospholipid and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) as in other systemic vasculitides and autoimmune diseases.

The venous and arterial wall lesions attract cytokinergic and neutrophilic reactions. The activated neutrophils leave destructive effect by excessive production of superoxide anion radicals and lysosomal enzymes. Neutrophilic infiltration and advanced vascular wall destruction with aneurysms formation cause local blood flow abnormalities. Endothelial dysfunction, release of von Willebrand factor, platelet activation, enhanced thrombin and fibrin generation, antithrombin deficiency and impaired fibrinolysis close pathological chain of enhanced thrombocoagulation associated with vasculitis (perivasculitis) in BD [36, 37]. Actually, pathological thrombosis in BD can be best viewed within the classical Virchow’s triad.

Estimates of cardiovascular involvement in BD reach 7-46%, with lethal outcomes in about 20% of severe cases [38]. As it is shown in multiple series of large observations, recurrent thrombophlebitis is the commonest vascular affection in BD [3]. Generally, venous involvement is reported in 29% and arterial in 8-16% of cases [39]. Affections of inferior vena cava and aorta bear the worst prognosis for patients with BD. Blood clots can develop in the deep veins of the lower extremity and migrate to the right heart and pulmonary arteries [40]. Destruction of elastic structures of aorta can result in formation of aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms prone to rupture. Aneurysms of smaller vessels can also develop, sometimes spontaneously. The risk of aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms is especially high in those, undergoing major (coronary artery bypass grafting, angioplasty of aorta and its branches) or even minor vascular interventions (e.g., arterial puncture) [8, 10, 41]. Coronary artery aneurysms are another major challenge in terms of diagnosis, cardiovascular risk assessment and treatment in BD. This type of coronary pathology clinically manifests as MI at a relatively young age without strong association with classical cardiovascular risk factors [10].

With the use of echocardiography other less frequent symptomatic or asymptomatic manifestations have also been reported (Table 1): pericarditis, endocarditis, myocarditis, ventricular thromboses (predominantly right-sided), cardiomyopathy with severe systolic dysfunction and valvular affections [38, 42].

Cardiac Manifestations in BD

| Detected by Echocardiography and MRI |

|---|

|

|

| Pericarditis |

| Interatrial septal aneurysms, left atrial dilatation |

| Left ventricular diastolic and systolic dysfunction |

| Endocarditis |

| Endomyocardial fibrosis |

| Right and left ventricular aneurysms and thrombi |

| Aneurysmatic enlargement of sinus valsalvae and ascending aorta |

| Mitral prolaps with or without regurgitation |

| Coronary aneurysms |

|

|

| Detected by Electrocardiography |

|

|

| Atrioventricular conduction disturbances (up to severe blockade and bradycardia) |

| Left and right bundle branches blockade |

| QT prolongation |

| Abnormal late potentials |

| Ectopic arrhythmias |

In our own practice, we have examined 44 patients with BD and cardiovascular involvement referred from ophthalmologists and dermatologists. To demonstrate complexity and variety of cardiovascular manifestations in BD, we present some cases from own practice.

Case 1

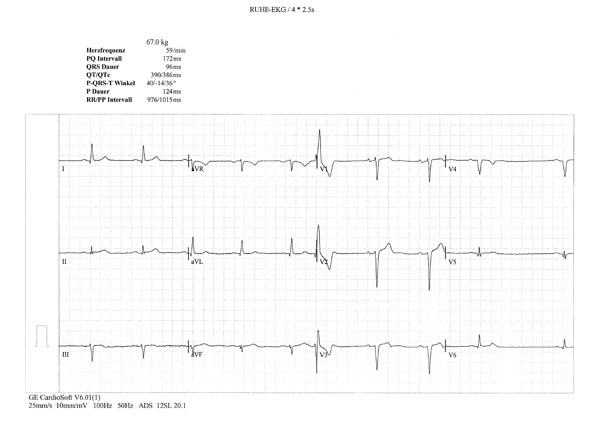

A 66-year-old male patient, who lived in Switzerland and whose parents were originally from Turkey and Azerbaijan, was diagnosed with BD in 2004, based on ocular symptoms, erythema nodosum, positive pathergy test and typical vasculitis described on biopsy specimens from erythematous area. The patient was treated with methotrexate, colchicine and corticosteroids with substantial improvement of ocular and mucocutaneous symptoms. In the absence of classical cardiovascular risk factors, the patient developed myocardial infarction with ST elevation (STEMI) and positive enzyme tests. On coronarography, large aneurismal lesions of left marginal and left descending coronary artery were detected. Coronary angioplasty was unsuccessful, with ventricular fibrillation requiring electrical cardioversion. Later, the patient was discharged from the hospital on aspirin, clopidogrel, beta-blocker and peripheral calcium-channel blocker, corticosteroids and cyclosporine. After 6 months, cyclosporine was discontinued because of worsened glomerular filtration rate and advanced heart failure (NYHA III). Importantly, at that time laboratory tests revealed high levels of proBNP (up to 2,246 pg/mL). On ECG performed in 2008, there were occasional extrasystoles and pathological Q waves (old anteroseptal MI) (Fig. 1a). Echocardiography revealed decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) (<36%), altered mitral flow [early diastolic/atrial flow (E/A)=0.5, fusion of E and A waves)]. MRI showed apical aneurysm with 2.5x2.3 cm calcified apical thrombus (Fig. 1b).

Occasional extrasystoles and pathological Q waves in the anterior and inferior leads.

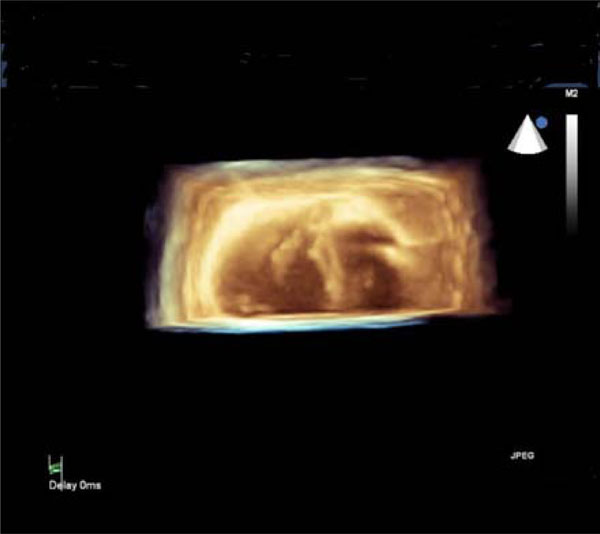

MRI image of enlarged left ventricle with a large intracardiac calcified thrombus.

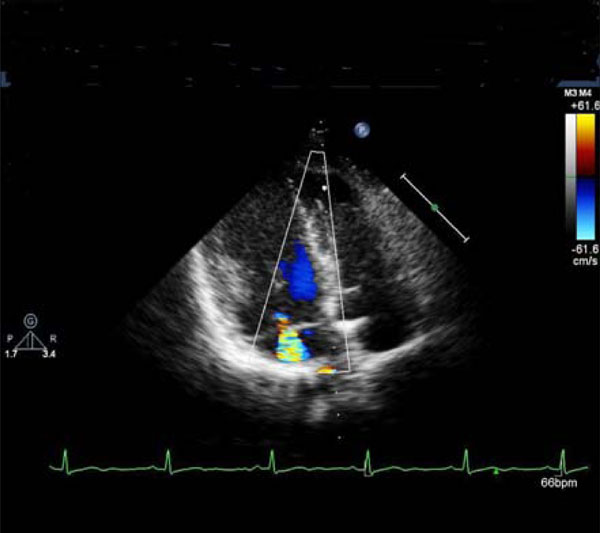

Mitral regurgitation.

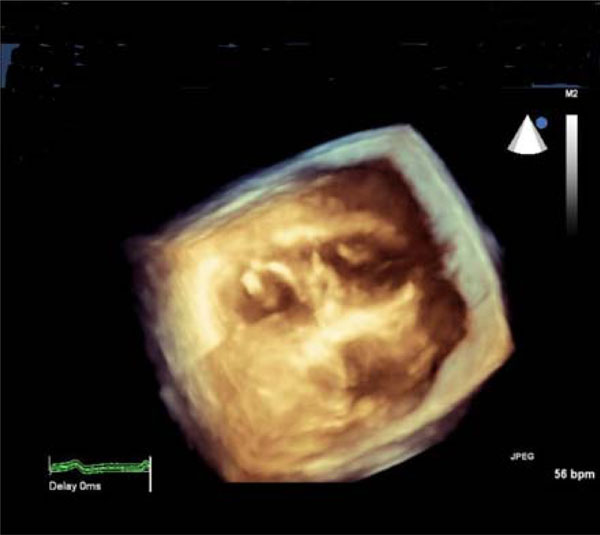

3D-echocardiographic cross-sectional image of the heart: thickened mitral valve (left-side) and papillary muscles of the tricuspid valve (right-side).

3D-echocardiographic cross-sectional image of the heart: thickened anterior papillary muscle of the mitral valve (left-side) and thickened papillary muscles of the tricuspid valve (right-side).

Myxoid mitral and aortic valves and enlarged sinus coronarius.

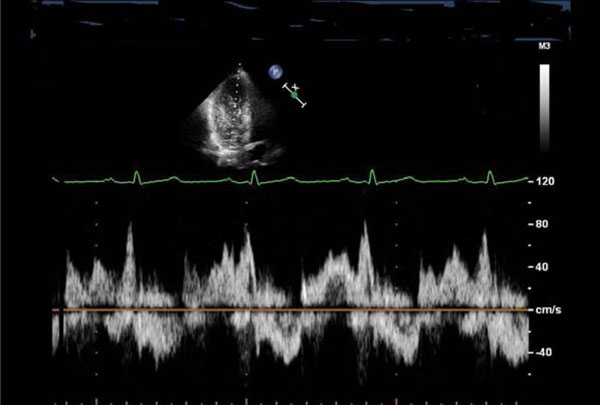

Transmitral blood flow suggestive of diastolic dysfunction (impaired relaxation): reduced E/A ratio, prolonged deceleration time of the E wave, and a fusion of E and A waves.

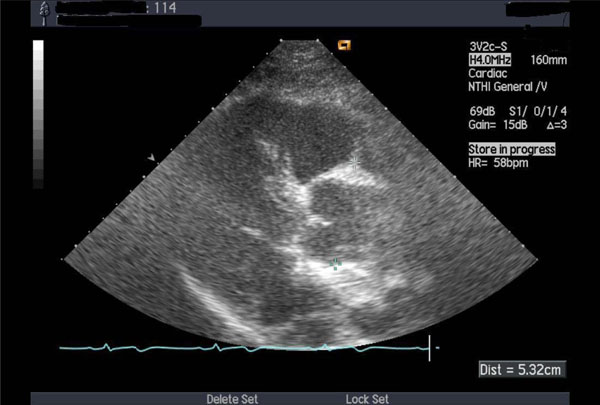

Thickened aortic valve and enlarged ascending aorta.

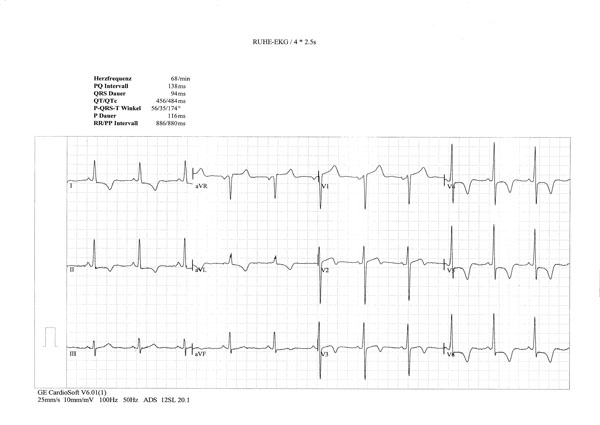

ECG signs of left ventricular hypertrophy; horizontal ST depression in I, II and V4-6 and giant inverted T waves in I, II, aVF, V4-6.

Case 2

A 52-year-old woman (Swiss father, Greek mother), living in Switzerland since the age of 32, was referred for consultation with established diagnosis of BD in 2002 (recurrent oral ulcerations, retino-uveitis, erythema nodosum, perivasculitis in biopsy specimens). The patient was treated with corticosteroids, methotrexate and colchicine. The cutaneous and mucosal pathology improved dramatically. In 2005, she experienced suddenly developed dyspnea (NYHA II-III) and palpitations. New heart murmurs were detected. Besides, there were also several other signs of cardiac pathology: pathologic right apical bulging; marked and permanent splitting of the 2nd heart sounds, 4/6 degree tricuspid, 3/6 degree mitral regurgitation murmur; 2/6 systolic aortic and 2/6 diastolic murmurs over aorta; premature beats (supraventricular and ventricular in origin) and complete right bundle branch block on ECG; aneurysmal motion of the interatrial septum, dilatation of the sinus coronarius, mild mitral regurgitation, myxoid mitral and tricuspid valves, enlarged annulus of the thickened aortic valve, and severe mitral regurgitation on echocardiography (Fig. 2 a, b, c). The calculated mean pulmonary pressure was 38 mmHg. Spiral CT excluded pulmonary lesions and embolization. The patient was treated with aspirin, diuretics and carvedilol. Occurrence of symptomatic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation and complex ventricular arrhythmias were successfully treated with amiodarone. Lately, the patient was asymptomatic and continued treatment with aspirin and carvedilol. On echocardiography there were features of myxoid mitral and tricuspid valves with insignificant mitral and moderate tricuspid regurgitation. The interatrial septum was thickened but without aneurysm. The mean pulmonary pressure was normal (18 mmHg).

Case 3

A 66-year-old female patient (father from Algeria, mother from Afghanistan), who had been living in Switzerland since the age of 24, was diagnosed with BD in 2003 (oral aphths, genital ulcers, phlebitis, erythema nodosum, positive pathergy test). She was treated with high-dose corticosteroids in combination with cyclophospamide and colchicine. Non-cardiac symptoms ameliorated. In 2005, she was diagnosed with heart failure. On physical examination – mitral and aortic regurgitation murmurs, on ECG – I degree AV blockade, left ventricular hypertrophy, non-specific ST changes; on echocardiography – II degree mitral and aortal regurgitation, enlarged sinus coronarius and aortic root (Fig. 3a), and diastolic dysfunction (Fig. 3b). Due to the worsening of mitral regurgitation, the patient underwent mitral valvuloplasty 3 years later.

Case 4

A 54-year-old Italian male patient was diagnosed with BD in 2002 (recurring genital ulcers, iridocyclitis, epididymitis, vasculitis with perivascular mononuclear infiltration on biopsy). He was treated with high-dose corticosteroids, methotrexate and colchicine with a substantial improvement of non-cardiac symptoms. In 2004, the patient presented with dyspnea (NYHA II) and diastolic murmur over the aorta. Echocardiography showed thickened aortic valve and mild dilatation of the ascending aorta (Fig. 4). There were also signs of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction with preserved systolic function. Candesartan and carvedilol were added to the treatment. Dyspnea disappeared. On echocardiography, performed 9 months later, there were no signs of aortic dilatation. Diastolic dysfunction disappeared two years later.

Case 5

A 55-year-old Greek male patient, who lived in Switzerland since the age of 20, was diagnosed with BD in 2002 (recurrent oral aphthous ulcerations, genital ulcers, phlebitis, erythema nodosum, positive pathergic test), and was treated with high-dose corticosteroids, methotrexate, colchicine. Non-cardiac symptoms responded to the treatment. ECG showed mild left ventricular hypertrophy with nonspecific changes of T wave. Two years later, the patient developed non-ischemic chest pain, dyspnea (NYHA II), and ECG revealed left ventricular hypertrophy, with marked horizontal ST depression in I, II and V4-6 leads, and giant, negative T waves in I, II, aVF, V4-6 (resembling changes of apical cardiomyopathy) (Fig. 5). On echocardiography there were signs of left ventricular medial and apical endocardial fibrosis with advanced diastolic dysfunction (similar to the changes in Fig. 3b). There was also blood pressure elevation from 130/80 mmHg (2002) to 160/100 mmHg (2004). Therapy with candesartan, amlodipine and carvedilol was initiated with blood pressure normalization and cardiac symptoms improvement. However, electrocardiographic and echocardiographic findings remained unchanged.

TREATMENT

Treatment of BD is still based on low level of evidence (experts’ opinion) [43]. Corticosteroids along with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, azathioprine, cyclosporine colchicine provide remissions of variable duration in most patients. Experience with the use of anti-TNF agents in BD has advanced in the past decade. Some studies and case reports are also suggestive of successful treatment of BD with thalidomide and lenalidomide [44, 45]. Colchicine was shown to be effective, particularly in cases of pericarditis, in numerous Middle Eastern observations. Oral anticoagulants and antiplatelets are often used to treat thromboembolic complications in BD. However, antithrombotic therapy should be administered cautiously, given the proneness of BD patients to bleedings, particularly from symptomatic or asymptomatic pulmonary aneurysms. From the other hand, combined therapy of thalidomide or lenalidomide with corticosteroids should be under scrutinized monitoring of thrombosis and coagulation markers, because of an associated substantially increased risk of deep vein thrombosis [46, 47].

Taken together, not much is known about efficacy and safety of treatment of cardiovascular manifestations in BD. Conventional drug treatment of acute coronary syndromes in BD, which can be caused by ruptured aneurysms, is not balanced against possible treatment induced hazards. Severe myocardial ischemia can be treated with coronary angioplasty. However, given the risk of spontaneous dissections and secondary aneurysms, this therapeutic option seems to be unsafe. Treatment of arrhythmias in BD is also challenged. One of the numerous serious issues is electroimpulse therapy with transient or permanent pacemakers, which can be complicated with secondary aneurysms.

CONCLUSIONS

Cardiovascular manifestations in BD are numerous, and their relationships with non-cardiac features are not well explored. Main cardiac features of BD include pericarditis, myocardial (diastolic and/or systolic dysfunction), valvular, coronary (thrombosis, aneurysms, rupture) and intracardiac thrombus (predominantly right-sided). Several cardiac manifestations may coincide in one patient. Cardiologists should always bear in mind potential threats of (a)symptomatic cardiovascular involvement in BD and consider non-invasive diagnostic measures (echocardiography, CT, MRI) for its timely detection. Treatment of cardiovascular manifestations is not well explored and there are still major concerns over the safety of drug treatments and angioplasties.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Assistance of Dr. David Chu with writing and editing the manuscript is acknowledged.