All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Life-threatening Rupture of a Femoral Pseudoaneurysm after Cardiac Catheterization

Abstract

A pseudoaneurysm refers to a defect in the arterial wall, allowing communication of arterial blood with the adjacent extra-luminal space. Pseudoaneurysms result from traumatic arterial injury. With the increasing utilization of percutaneous arterial interventions, iatrogenic arterial injury has become the predominant cause of pseudoaneurysm formation. Rupture of the pseudoaneurysm comprises a vascular emergency. Clinical suspicion and imaging techniques are the cornerstones of timely diagnosis and appropriate management of the condition. Herein, we report the case of a 69 year-old woman who suffered a life-threatening profunda femoral artery pseudoaneurysm rupture after a routine cardiac catheterization, that was treated surgically.

CASE PRESENTATION

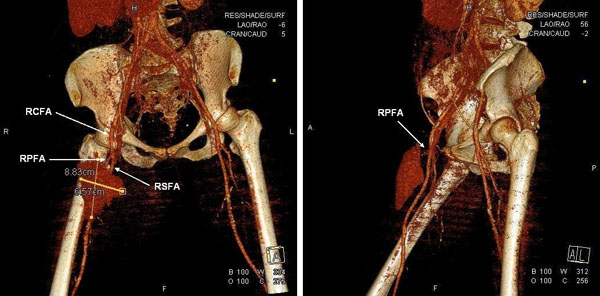

A 69 year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for a preoperative coronary arteriography. The patient was scheduled for aortic and mitral valve replacement due to severe and symptomatic aortic stenosis and mitral insufficiency, respectively. Thirty-two years prior, she underwent mitral valve replacement with a bileaflet mechanical valve for mitral stenosis of rheumatic etiology. On admission, the patient was hemodynamically and clinically stable. She underwent an uneventfull coronary arteriography, via a 6F right femoral sheath and the usage of standard Judkins catheters, which demonstrated normal coronary arteries. The patient was scheduled to be discharged on the next day. However, about 6 hours after sheath removal, the patient experienced severe sharp pain in the right anterior femoral region, without reported numbness, tingling, or loss of voluntary movement. Physical examination revealed severe hypotension and a mass in the right femoral region, without any discoloration of the extremity. Emergency multislice computed tomography and computed tomographic angiography of the lower abdomen and the right lower extremity demonstrated two voluminous hematomas at the anterior femoral (Fig. 1A, B & Fig. 2) and internal femoral (Fig. 1C, D) surfaces with 7.8x4.6x10.5 cm and 12x8.5x9.7 cm dimensions, respectively. The anterior hematoma was ruptured and exhibited active bleeding from the right profunda femoris artery (RPFA). There was no retroperitoneal hematoma. The patient was administered normal saline solution and dobutamine intravenously for hemodynamic support and was transfered to the intensive care unit. With the diagnosis of a ruptured pseudoaneurysm confirmed and the hemodynamic deterioration of the patient worsening, ultrasound-guided thrombin injection was considered inappropriate and emergency surgery was performed. RPFA was sutured at the site of bleeding and the hematoma was evacuated. Apart from two units of red blood cell transfusion due to an 8% drop in hematocrit, the patient had an uncomplicated post-operative course. A repeat computed tomography scan of the operated region showed no pathology and the patient was discharged a few days later with instructions for reassessment and rescheduling of the initial cardiac surgery.

DISCUSSION

A pseudoaneurysm is defined as a defect in the arterial wall, that allows communication of arterial blood with the adjacent extra-luminal space. In that case, blood is extravasating, however it is contained by the surrounding soft tissues and the compressed thrombus, thus forming a sac or cavity [1].

Traumatic arterial injury is the major cause of pseudoaneurysms. In these respects, the high utilization of percutaneous arterial interventions is responsible for iatrogenic arterial injury being the predominant cause of pseudoaneurysm formation [2]. The condition prolongs hospitalization, consumes health-care resources, and results in significant morbidity [3]. Furthermore, femoral pseudoaneurysms are reported to occur in 1% of diagnostic arterio-grams and up to 8% of therapeutic endovascular interventions [4].

Factors which may increase the risk of iatrogenic femoral pseudoaneurysm formation after femoral artery cannulation can be broadly categorized into procedural or patient factors. Procedural factors include low femoral puncture, inadvertent catheterization of the superficial femoral artery or profunda femoris artery, interventional rather than diagnostic procedures, and inadequate compression following removal of the arterial sheath. Patient factors include obesity, hypertension, calcified arteries, abberant anatomy with high branching common femoral artery, as well as the need for post-procedural anticoagulation [5].

Patients with femoral pseudoaneurysms typically present with pain and edema of the affected groin, along with a pulpable mass which may be pulsatile with a thrill or bruit. However, when the pseudoaneurysm involves the profunda femoris artery, or in obese patients, clinical diagnosis can be quite difficult and a high index of suspicion is required to prompt further investigation. Small pseudoaneurysms may resolve spontaneously without intervention. On the contrary, persistent pseudoaneurysms may enlarge and lead to complications related to compression of the adjacent femoral vein, nerve and overlying skin. This may cause leg edema, deep vein thrombosis, compressive neuropathy and skin necrosis.

Rupture of femoral pseudoaneurysms has been scarcely reported in the medical literature, either due to the rarity of the condition or the unwillingness to report a major iatrogenic complication. There has been a report of ruptured pseudoaneurysm after femoral arterial catheterization for continuous hemodynamic monitoring and multiple blood sampling, in a patient hospitalized in the intensive care unit [6], as well as a post-atherectomy superficial femoral artery pseudoaneurysm [7]. There have also been reports of ruptured femoral artery pseudoaneurysms, complicated with infection in drug addicts [8-10].

Duplex ultrasonography (DUS) is the modality of choice for the diagnosis of femoral pseudoaneurysms, with a reported sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 97% [11]. On DUS, a pseudoaneurysm appears as a hypoechoic sac adjacent to the affected artery, with colour flow observed within it. The hallamark of diagnosis is the demonstration of a neck communicating between the sac and the affected artery, with a “to-and-fro” waveform. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is also a valuable diagnostic tool. CTA allows accurate assessment of the pseudoaneurysm, its surrounding structures, arterial inflow and distal run-off of the leg [4]. In recent years, gadolinium enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) has emerged as an alternative to CTA in the diagnosis and characterization of femoral pseudoaneurysms [12].

Approach to the management of a pseudoaneurysm depends on its anatomical location. Treatment of femoral pseudoaneurysms can be classified into the following: radiological management, including ultrasound guided compression repair (UGCR) [13], endovascular management, with the usage of embolization [14], perfusion balloons [15], and placement of covered stents/endoluminal prostheses [16]. However, when there is evidence that the femoral pseudoaneusysm is ruptured, as in our case, surgery is the cornerstone of treatment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.